2011 Civil War Travelogue, Part 2

Welcome to my 2011 travelogue page, commemorating the first year of the Civil War Sesquicentennial! This is Part 2 of 2011. Go to Part 1 (includes an index of all the 2011 trips). Go to Part 3. Go to Part 4. Go to Part 5.

| Here is a reminder about the reason I write these pages the way I do. They record my experiences and impressions of Civil War trips primarily for my future use. Thus, they sometimes make assumptions about things I already know and focus on insights that I receive. They are not general-purpose descriptions for people unfamiliar with the Civil War, although I do link to various Wikipedia articles throughout. Apologies about the quality of interior photographs—I don't take fancy cameras with big flashes to these events. If you would like to be notified of new travelogues, connect to me via Facebook. |

BGES Walking Tour of Chancellorsville, May 27–30

I attended a walking tour of Chancellorsville with the Blue and Gray Education Society. (I wrote the Wikipedia article, Battle of Chancellorsville, and most of the other Wikipedia articles linked here. Links to biographies of most of the generals referred to here can be found in that article.)

Friday, May 27

I arrived late last night through Dulles and checked into the Comfort Inn, Southpointe, on the southern outskirts of Fredericksburg. Today the BGES program does not start until 6 PM, so I fooled around for the day. (Given the flight schedules from San Francisco, it would not have been possible to fly out Friday and still make the evening session.) I decided to hit the southern end of the Fredericksburg battlefield, an area that my last comprehensive tour of Fredericksburg didn't cover for some reason (well, I guess time constraint was the reason). By coincidence, the Civil War Trust published their second iPhone battle app, and it was about Fredericksburg! I downloaded over 140 MB on the rickety hotel WiFi and set out to Lee Drive, just south of the visitor center. I found the CWT app to be not very useful if you do not have the NPS map to follow. They have directions that make reference to locations not represented by signs on the battlefield road, so I spent about 20 minutes in confusion. I was able to see a short video of Frank O'Reilly uncomfortably describing the breakthrough of Meade's troops and the shooting of Maxcy Gregg. And the GPS function seemed to work okay, but I did not otherwise enjoy using the app enough to buy another one.

I climbed up to the top of Lee's Hill, where Robert E. Lee observed the battle of Fredericksburg. Fortunately for him, he had Confederate Army engineers to cut down all the trees in the way of his view, but those engineers have long since passed away, and the modern visitor can't really see much of anything in the summer. In theory, you should be able to see the entire battlefield from that location. I stopped at Howison's Hill and looked at what they implied was a 30-pound Parrott rifle (although I would have guessed it was a 20-pounder), brought in from Richmond given the extra time they had while Ambrose Burnside was dithering on the other side of the river. I drove along long sections of Jackson's line and was impressed about how well preserved the trenches are. I have to wonder whether they were actually reconstructed. I stopped to take a photograph of Meade's Pyramid, which was erected as a tourist monument by the railroad, and then went to the end of the Confederate line on Prospect Hill. I also walked down a dirt path to reach Hamilton's Crossing, which was a thriving railroad supply stop at the time, but now has nothing to speak of.

Then I drove across the Rappahannock River and visited the White Oak Museum in Falmouth. It is small, but they have an astonishing volume of artifacts—many tens of thousands—recovered from the battles and camps of Stafford County. Bullets, belt buckles, buttons, shells, tools, you name it. There was a display of stone arrowheads that I considered joking with the attendant about, but he seemed pretty no-nonsense. They also have a room with an extensive library where you can research unit histories. Garry Adelman recently published a book for the CWT that said this museum is one of the 150 things you should do during the Sesquicentennial, so I that's now off my bucket list. I had lunch at a sandwich shop in downtown Fredericksburg, which is a cute little city. I visited a couple of bookstores and art galleries. I found a book that interested me, but before I bought it I had the presence of mind to check my online list and found that I already owned it! I enjoyed seeing all of the paintings of Confederate apotheoses (and Saint Joshua Chamberlain too, of course), and had my eye on a handsome portrait of Stonewall Jackson, but if I had a dog house at home, both I and that painting would be living there after my wife saw it.

Capitalizing on my Jackson swoon, I decided to revisit his shrine in Guinea Station, about 15 minutes to the south. I first visited there in 2004, but my web travelogues were so skimpy back then that I won't even bother including a link here. I have a vague recollection that I was unable to enter the house where he died, but this time it was open and I visited all of the rooms, seeing the bed in which he supposedly died and the sleeping quarters of all of his staff. I found out that the main house of the plantation, the Chandler residence, was too noisy for Jackson, or perhaps for Dr. Maguire, so they used an out building. It's a good thing because the main residence burned down in later years. Pilgrims would have no place to worship. I had an interesting conversation with the lonely park ranger about the relative merits of Jackson and Longstreet. I will leave it as an exercise for the reader to determine which general he favored. (My feelings are a bit more mixed.) I also had the satisfaction of hearing a conversation with a tourist who wanted directions to North Anna and Totopotomoy Creek, but the ranger had none of the Virginia Civil War Trails maps available. I, on the other hand, had the foresight to store a PDF version of that very map on my new iPad (I have over 200 maps on that sucker!), so I emerged the hero and my recent purchase of said gadget was well justified.

I drove back in the direction of Spotsylvania Court House and spent some time at Laurel Hill. This was a very important sector in the 1864 battle and, even though I visited just last year, I wanted to get another look. Unfortunately, virtually all of the wayside signs were down for maintenance, so I had to use my imagination a bit. I also have to beg some forgiveness from users of my battle maps, where I show Laurel Hill as a real, although minor, hill. However, it has even less of a slope than Cemetery Ridge. So I had to employ some cartography artistic license. If the map showed humidity instead of elevation, there would have been a prominent feature depicted on the path of my walk. :-)

Our BGES program started at 6 PM in the hotel. We have 11 attendees, led by Len Riedel, executive director of the society. Originally Mike Miller of the Marine Corps was going to join us as historian, but he had a conflict, so the whole program is on Len's back. What makes it more difficult for him is he just returned from a European trip and is pretty jetlagged. We spent about an hour and a half talking about the background to the campaign and Len was able to do a very credible job without notes or visual aids. One of the things I found interesting was that Robert E. Lee was planning to invade the North (for a second time) earlier than I was aware. He issued orders on March 20, 1863, to prepare to march starting on May 1. He did not anticipate Joe Hooker's plan and in fact expected Wilmington, North Carolina, to be the target of the late spring offensive. That was a primary reason that two divisions from Longstreet's corps were in southeastern Virginia. One of the key points of the evening was to emphasize the reorganization of intelligence resources in the Union Army. The group also had a discussion denigrating the communications during the battle. As a former Signal Corps officer, I derive some satisfaction that it was the separate Military Telegraph Service that caused a lot of the difficulties. After the session at the hotel we adjourned to the nearby Cracker Barrel restaurant for dinner. I think that every BGES session I have ever attended featured a Cracker Barrel dinner. Len must qualify as a corporate hero to them.

Saturday, May 28

We started our walking tour of Chancellorsville with one heck of a lot of driving. We had a nominally 15-passenger van that was pretty crowded, but once again Len granted me the courtesy of sitting in the front seat because of my long legs. In the morning we concentrated on the defensive strategy of Robert E. Lee, examining the 25 miles he defended on the Rappahannock River. The key characteristic was the relatively high ground just to the west of the river along this entire 25-mile line, so Lee could keep some areas lightly defended and rely upon the terrain to retain an advantage. Meanwhile, he had Stonewall Jackson's corps in a centralized location so that they could respond quickly to any Federal incursions. We began at Lee's left flank, viewing the river and the high ground between Banks's and Scott's Fords. The river banks were really quite dramatic and it is very difficult to understand how they were able to move large numbers of troops and equipment through these narrow, steep corridors. We moved into Fredericksburg and stopped at Old Mill Park, where we had a good view of Stafford Heights on the other side of the river, the high ground that gave the Federals an advantage in terms of an artillery platform. Before the battle started, the opposite bank represented Hooker's right flank. We drove to the base of Lee's Hill. I reported on my reconnaissance yesterday and no one felt like hoofing to the top to be rewarded with no view. We drove to the Slaughter Pen Farm, which is the famous recent addition to the battlefield by the Civil War Trust, and discussed how Lee entrusted this entire sector to two divisions, under McLaws and Anderson. It was interesting to see here that there was a Fort Hood in Fredericksburg, which was constructed in November 1862 to interdict Union gunboat traffic on the Rappahannock. We also had a look at the marker commemorating Major John Pelham's heroic artillery stand during the battle of Fredericksburg.

We headed to the east and stopped briefly at locations where Stonewall Jackson's division commanders had their camps, positioned so that they could quickly march to where they needed to go. We went to Moss Neck, which was Jackson's headquarters, but it is private property and we did not really see anything. Next was Skinker's Neck, which is a tight loop in the river. Robert E. Lee thought that there was a good chance the Federals would attack in this sector, so we wanted to have a good look at Hooker's options. We determined that crossing the river at this point would have been feasible enough, particularly because the Union Navy would be able to assist, but at the base of the loop there was that high ground again and taking it would have been very costly. The entire area surrounded by the river was like a natural bowl. We drove around hoping to find a good view of the river close up, but never got direct contact. We did find a line of Confederate trenches in the woods, which had an interesting sharp angle. We determined from road traces that it was probably protecting a crossroads of the time. The line of hills that Lee was using for his defense petered out at the town of Port Royal and we drove around there a little, observing many 18th century homes that were in a state of bad repair. Len told us that anyone willing to rehabilitate these properties would be able to acquire them for a song. We then headed north over the river looking for lunch and eventually found a whole row of fast food restaurants near the Dahlgren Naval Weapons Station on the Potomac.

After lunch we concentrated on the Federal positions. We stopped at Lamb's Creek Church, directly north of Skinker's Neck, which was essentially Hooker's left flank, about where John Sedgwick's VI Corps camped for the winter. It looked quite ancient, but it had a modern Episcopal Church sign out front, so perhaps it's still in use. We found the area where Hooker's headquarters had been located, although it has been obliterated by a housing development. It was only a few blocks away from the museum I visited yesterday. We drove out to Potomac Creek, where the Belle Plains landing was used to supply the Union Army with hundreds of tons of food and supplies daily. (Robert E. Lee had nowhere near this luxury of ample supplies being delivered.)

Our final activity was to return to some of the fords over the Rappahannock, seeing where the infamous Mud March occurred. (In January 1863, following his failure at the battle of Fredericksburg, Ambrose Burnside attempted another offensive that would cross Banks's or U.S. Ford and attempt to get into the rear of the Confederate Army, somewhat similar to what would occur in May at Chancellorsville. However, the attempt was a complete failure because heavy rains thawed out the frozen roads and turned them into morasses of mud. The advance was recalled and Burnside was quickly replaced as commander of the Army of the Potomac.) We were all very impressed at how difficult the terrain was in approaching these fords. We had enough difficulty walking partway down to them under dry conditions. In the rain and mud, it must have been torture. This part of the day became somewhat of an adventure because Len had not pre-visited either ford. Trying to find Banks's Ford, we wandered onto the Cannon Ridge Golf Course. The Google GPS map application on my iPhone showed a road that we could use to get there, but it turned out to be a rough dirt road, so we bravely bounced along in our 15 passenger van. Eventually we reached a point where we had to cross a golf fairway on foot, and we were rewarded by finding three pristine artillery lunettes, which had been constructed by the Union Army after the battle. We tried to walk through the woods to get to the river bank, but the slope was too steep. We were eventually rescued by a cute young girl in a golf cart who was selling beers and sodas.

The dirt road across the golf course.

Attempting to find U.S. Ford, we took a small road that ended up in a family's yard and it turned out that the ford was on their property. We had to hike down a steep, slippery dirt road, accompanied by the family's friendly black Labrador. At the bottom we encountered two good old boys who were sitting in their Jeep drinking beer. They were not entirely forthcoming with the story of how they were able to get the Jeep down to this location, so we suspect that they went through some areas they were not really allowed to be in. There is a large pipeline that crosses underneath the river and there is a road that goes down parallel to it, but I do not think it is open to the public. This time we did make it to the river bank and were almost able to see the confluence of the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers. Once again, it's really difficult to imagine taking wagons and artillery pieces over the approaches to these fords, even under good weather conditions. (Speaking of which, we had very good weather all day, albeit a bit hot.)

We did not achieve our full hoped-for itinerary today. The original plan was to finish up at Kelly's Ford, site of the March 17 battle and a crossing point for Chancellorsville. We were all a bit tired from driving around all day and decided to postpone it until Sunday morning. After returning to the hotel and inspecting ourselves for ticks, a subset of us went out for a non-hosted dinner. We ended up in a small pizza/pasta place called Grioli's, which I would not recommend.

Sunday, May 29

Once again, we did a lot of driving today, although everyone appreciated it because the weather has turned really hot—mid-90s. We started at the Slaughter Pen Farm to discuss Hooker's plan and Lee's reaction. Lee had been confident enough with the strength of his positions to send one third of his army away (two of Longstreet's divisions). Hooker wanted his force in front of Fredericksburg to catch Lee's attention, and it worked. Both Lee and Stonewall Jackson assumed that the initial movement by John Sedgwick was to be the main effort by the Federal army and Lee ordered Jackson's divisions to move from their staging areas. We drove to Aquia Creek to see the camps of the XI and XII Corps and the big supply depot there, which was the starting point of the large Union flanking movement. We follow the route of Slocum's XII Corps through Stafford and to Hartwood Church, where they stopped for the night. The church was also the location of a cavalry raid on February 25 in which Fitzhugh Lee routed some Union vedettes. The next day of marching took the XII Corps to Mount Holly Church, for a total of 30 miles in two days. Hooker had successfully deceived the Confederates into thinking he was sending a force into the Shenandoah Valley. He knew that the Confederates had broken one of the Union signaling codes and used that knowledge to send them disinformation. Our next stop was Kelly's Ford, not too far from Brandy Station, where in retaliation for the Hartwood Church raid, William W. Averell instigated the battle of Kelly's Ford. We discussed the raid in a little detail. There were two significant aspects: the Union cavalry achieved a boost in morale by aggressively challenging the Confederates, and Major John Pelham, the young Confederate star artillerist, was killed.

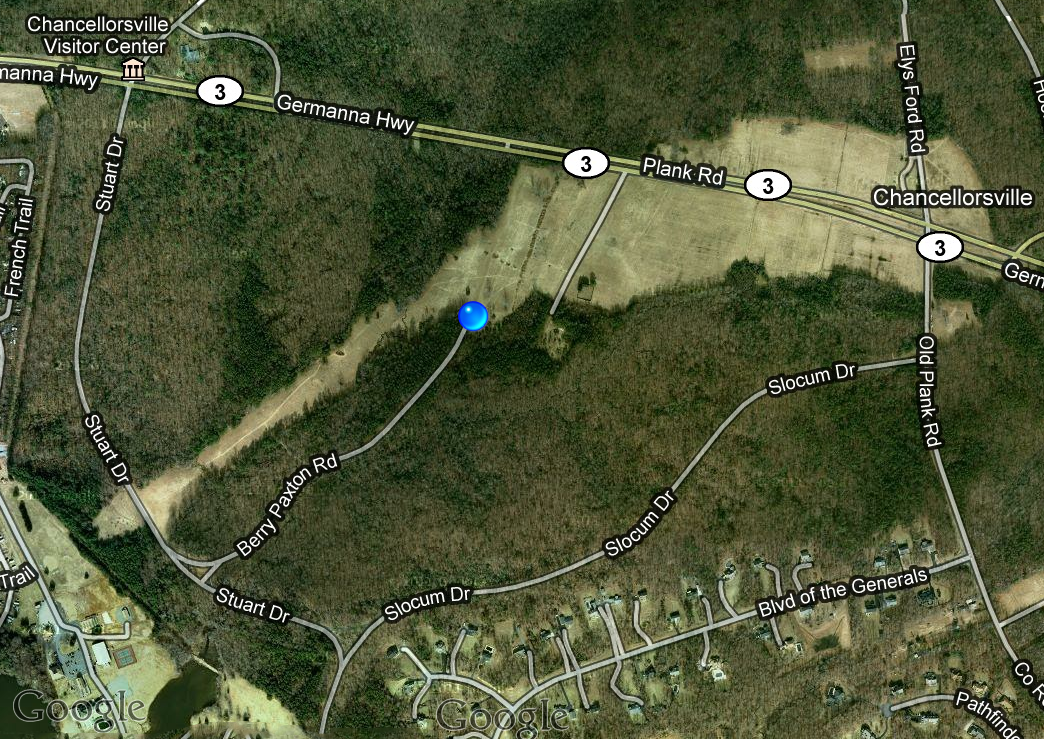

We followed Meade's V Corps across Eli's Ford (spelled Eley's on road signs today); the XI and XII Corps crossed upriver at Germanna Ford, which we did not see. This brought us onto the Chancellorsville battlefield after noon. As we discussed the reaction of the Confederates, we criticized the inflexibility of Hooker's planning. He essentially had two plans in mind: Plan A was for Robert E. Lee to "flee ingloriously"; Plan B was for Hooker to get into a good position and receive an attack. Hooker did not have a response to what turned out to be Plan C: dealing with an immediate attack from Lee. We visited Tabernacle Church, which was Stonewall Jackson's headquarters on May 1, and drove up River Road, which was taken by two divisions of Meade's Corps almost as far as Banks's Ford. Then we drove to the Orange Plank Road (Virginia Route 3) to visit the Civil War Trust's recently acquired area commemorating the May 1 battle. They have a lengthy walking path, for which our walking tour of Chancellorsville did not have time to walk. My friend Harry had arrived early and walked this two days previously, reporting that the 90 minutes estimated by the CWT was actually closer to three hours.

We drove to the Lee-Jackson Bivouac park tour stop, where the two generals met the night of May 1 to plan Jackson's famous flanking march. We did not spend a lot of time assessing blame for the poor Federal response to the flanking march, noting primarily that the I Corps of John F. Reynolds had been delayed in arriving from south of Fredericksburg, taking a long march that eventually crossed US Ford, destined to take up a position to the right of the XI Corps, thereby anchoring the Union right at Eli's Ford. Len portrayed the flanking march to be primarily Stonewall Jackson's idea, although I have seen alternative accounts. We then drove on the flanking march route, including a look at why the detour was required from the Brock Road to avoid being sighted. We ended up in a small private cemetery, which was the unanchored right flank of the XI Corps. Len said that the Park Service interprets that position as being farther to the east, most likely to keep hordes of tourists out of the cemetery. By coincidence, we arrived at about the same time that Jackson's men started their attack, about 5:30 PM. (Of course, we are on daylight saving time now, so we were actually an hour off in terms of daylight.)

We did not follow Jackson's attack on foot (which one might have expected on a walking tour), but had a good discussion and made a few stops with the van. We got a good idea of the breadth of the attacking line and saw how the different terrain features caused the attackers to funnel into a narrower front as they progressed. Len told us that Jackson's objective was to push as far as the US Ford to cut off the Union line of communications. We visited the ruins of the Wilderness Tavern, which served as a hospital after the attack. One of the guys on the tour had an ancestor from Alabama who was wounded during the attack and he was probably treated in this building, along with Stonewall Jackson later that evening. We visited the final line of the XI Corps, near Dowdall's Tavern, east of Wilderness Church. We took a break to go to dinner at Chili's and then returned to the visitor center at about 9:30 PM. The center was closed, of course, but we wanted to stand outside nearby to discuss the shooting of Stonewall Jackson. There was a lively argument about the position in which he stood in relationship to the North Carolina troops who accidentally shot him. Len thought that it was unlikely he was shot from 300 yards away, although a number of us maintained that accuracy is not much of a factor in an accidental shooting, range is. On the way back to the hotel, Len entertained us by driving through the pitch black park without headlights for a ways, demonstrating how difficult it was for Dan Sickles's III Corps to make their midnight attack. Everyone was pretty tired out by the time we finished for the day.

Monday, May 30

Happy Memorial Day! Today is even hotter, peaking high in the upper 90s. It was over 80° by 9 AM. We adjusted our walking expectations a bit to adjust for the heat situation. We started with a discussion of the attacks against the Confederate rear guard on the afternoon of May 2, as Jackson passed by on his march. Folks were unimpressed by Sickles's attack, which took 4 to 5 hours and accomplished very little. We opined that it could have been just as important as the Jackson flanking march if they had aggressively attacked the Confederates remaining in that area. We drove to Hazel Grove, the important artillery position, and discussed its terrain. The high ground on which it stood is actually a larger area than is currently cleared off by the Park Service. And the part that is not cleared off consists of trees 90 feet high, versus the 12 foot trees that were common during the battle. We drove to the ruins of the Chancellor house (actually just a little bit of foundation) and used some detailed maps to outline Jeb Stuart's attack of May 3. Hooker's decision to withdraw Sickles from Hazel Grove was an obvious problem and Edward Porter Alexander took full advantage of it by placing over 40 guns on that high ground. In midmorning, Hooker suffered a concussion from a cannonball that struck a post he was leaning against, and that effectively left the Federal army without its head. He had been rather secretive with his key subordinates about his intentions for strategy, so they were at a loss. And even though he was partially incapacitated, he refused to turn over command to his senior subordinate, II Corps commander Darius Couch.

We took a rest break by visiting the park visitor center, and browsed through their bookstore. Then it was outside into the heat again, visiting Fairview, which was the Union artillery position about a mile from Hazel Grove, that suffered from the superior position the Confederates possessed. We walked along the line of the XII Corps, and found a few remains of earthworks. Back in the van, we drove back past the Union line to examine the more compact salient that was set up after the Federals lost the Chancellorsville intersection. Once again my GPS was employed to help us find the closest point to US Ford (the southern end this time), but we ended up on some private property and chose not to push our luck for the final half mile to the river. It was time for lunch and we spent a leisurely time at TGI Friday's, escaping from the heat, but mostly because of slow service. We then had a couple of hours to finish up the campaign.

We drove to Salem Church and discussed the May 3–4 battle. Sedgwick had finally taken Fredericksburg and started to move east to threaten Robert E. Lee's rear, but Lee sent Lafayette McLaws to intercept him, and successfully stopped the advance. There was very little to see because the church has been completely surrounded by dense commercial development, but the action was relatively straightforward, with two long lines fighting each other head-on. One of the interesting things I learned here was that Hooker considered sending a force across Banks's Ford to swing around and attack Lee in the rear.

Photo courtesy of Harry Thaete

Moving east, we returned to Fredericksburg and drove on Lee Drive again, discussing how Jubal Early's defensive line was laid out. I found out that all of the trenches I had seen here a few days earlier were actually dug after the 1862 Fredericksburg battle. Then we visited the Slaughter Pen Farm for the third time, this time to discuss Sedgwick's positions and his movement into Fredericksburg. We drove around downtown Fredericksburg for a while and then to the visitor center and famous stone wall. By this time, everyone had run out of steam and we had little discussion of the second battle of Fredericksburg. We pretty much just hung out at the bookstore for a while and then drove back to the hotel. A few of us had dinner at Famous Dave's, my favorite barbeque chain.

I had a very good time on this BGES adventure, as usual. Len Riedel is to be commended for putting together a quality program in the face of a last-minute cancellation by his principal historian. I would have preferred more organized walking on the battlefield and a bit less driving around in a van, although I understand how the constraints of the weather affected the touring strategy. It probably would have been more accurate to call this tour an "Overview of the Chancellorsville Campaign" because considerable time was spent on campaign planning and movement to the battlefield, relatively more than the examination of tactical considerations on the battlefield itself. Given my interest in the Civil War, that is a pretty good focus for me anyway. I look forward to future BGES outings. I have already committed to join Len and Parker Hills at Chattanooga this November.

My next Civil War trip will be June 26–30, for the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College. See Part 3 of my 2011 travelogue.