Hal Jespersen's World War II Japan Tour, October 2025 [Part 2]

This is my (Hal’s) report on a trip to study World War II in Japan and Okinawa, sponsored by the National WWII Museum. It is my second World War II trip with this organization. (The first, to study the US Eighth Air Force in England, is described here.)

Since this is a lengthy report, I have divided it into two pages.

Contents – Part 2

Saturday, October 4 — Hiroshima

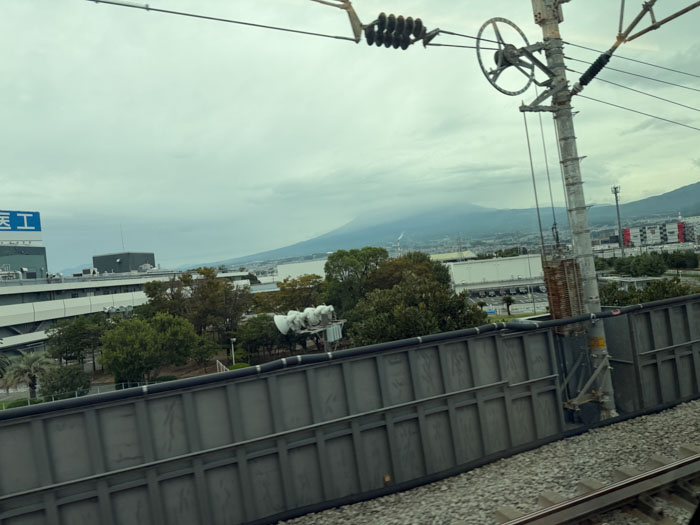

We bused to Tokyo Station for the 09:12 Shinkansen bullet train with service to Hiroshima. On the bus, I got Yasiko to talk about earthquakes, and she told us that Japan has 111 active volcanoes, and Mt. Fuji is overdue for eruption, which it does every 300 years. Our train left precisely on time and made seven stops before Hiroshima, three hours and 52 minutes later. Outside the metro areas, the train sped along at 285–300 kph. Seating was rather utilitarian but with good recline and excellent legroom. There was very spotty Wi-Fi service. (There is a “green car” first-class option with more comfortable seats and some meal service, but the museum did not spring for that.) We passed by Mt. Fuji, but clouds covered its top half. By the time we arrived in Hiroshima, my butt was numb; the experience was comparable to an exit-row seat in a 737, but with a harder seat cushion.

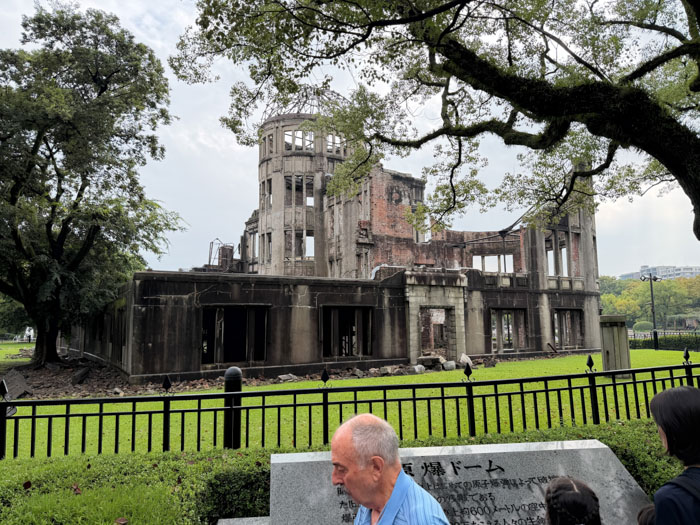

The Sheraton Grand hotel is connected to the train station. We walked over and had a decent buffet lunch. I found it a bit odd because about a third of the dishes were German. Maybe they’re trying to retain allegiance to their former Axis partners. Boarding the bus, we met our tour guide for the next three days, Koji-san. His English was moderately good, although his narration consisted primarily of reading from a script. We drove to the "T Bridge," which was the aiming point for the atomic bomb, and walked to the Bomb Dome building built in 1915. The hypocenter of the explosion was about 250 yards away. This was a controversial building because some residents wanted to tear it down to erase bad memories, and others wanted to preserve it in its ruined state. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Jon Parshall talked for a bit and imparted some information that I had not known: Hiroshima was the headquarters of the 2nd General Army, and there were at least 40,000 soldiers in the city at the time of the bombing; 20,000 of them died. This belies the common claim that the bombing was strictly against a civilian target.

The weather reports suggested moderate to heavy rain all day in Hiroshima, but it turned out it was simply overcast and quite humid. We walked to the Peace Park, which before the bombing was a bustling neighborhood with a population of over 4,000 people, but was totally obliterated. At the Children's Peace Monument, Koji told the story of a girl who developed leukemia from radiation and folded 1,300 origami cranes, which is supposed to grant you a wish, but then she died. The statue depicts the girl holding a crane, and there are numerous very colorful collections of cranes spliced together into rope-like forms. Next was the memorial mound, which had been a cremation site after the bombing. A monument to Korean victims featured a turtle, which is a symbol for longevity; 20,000 Koreans were victims of the bombing. Next was a building called the Rest House, which at the time of the bombing was a kimono factory. Thirty-six employees upstairs were instantly killed, but one employee, Eizō Nomura, happened to go down to the basement for some papers and survived, living until his 80s. The building is now a memorial, and the basement has been preserved. It features displays with text from his account of the day and the aftermath. We headed toward the Peace Memorial Museum. Along the way, we passed by the Flame of Peace and a cenotaph for the victims of the bombing. Their remains are buried underneath, and the names of 350,000 people are recorded inside.

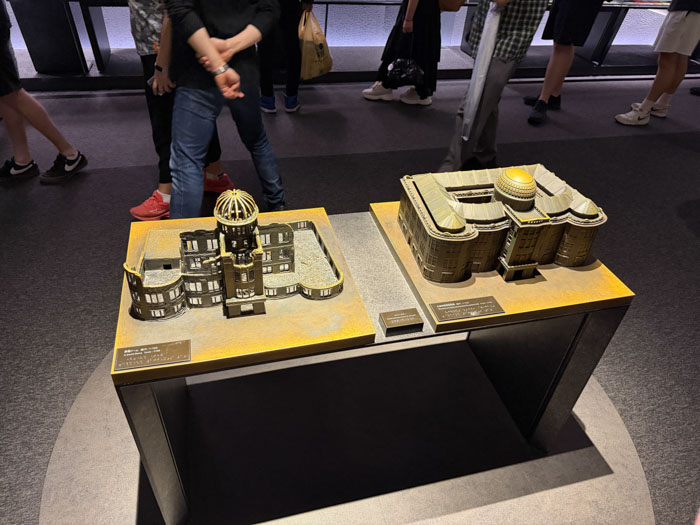

The museum is nicely done, although it is depressing in a way that you can certainly imagine. I was impressed at the ample translations of all the exhibits and the fact that I found no factual errors regarding the development or deployment of the atomic weapons. In addition to information about the bombing and its immediate aftermath, there is also a section about nuclear proliferation and peace movements.

Back at the hotel, we found our baggage from Tokyo in our (very nice) rooms and then proceeded to a lecture by Jon in which he outlined the three major ways in which the war could have ended—blockade and continued bombardment, US invasion, atomic bomb—and he calculated what the death toll would have been for each, including not only US and Japanese soldiers but also Japanese, Chinese, and other Allied civilians, who at that time were dying at the rate of 700,000 per month. The blockade scenario would have taken about 10 million lives, and the invasion 10-20. So, even generously assuming that the two atomic bombings resulted in 400-500,000 eventual deaths, the moral choice was clear.

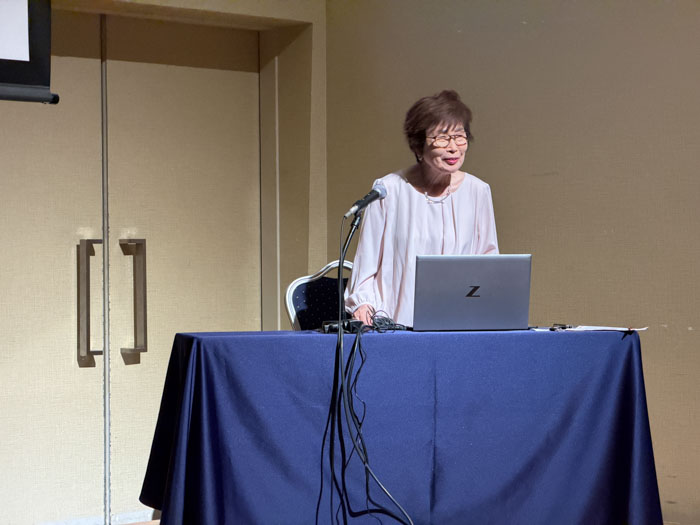

Then we heard from a truly remarkable person, Keiko Ogura, a survivor of the atomic attack, eight years old at the time (88 today, but remarkably well preserved). She was about a mile and a half away from the hypocenter, behind a hill, when the bomb went off. She told the story about how her father suspected something was going to happen and did not allow her to go to school that day. All of her schoolmates were killed in the explosion. She had harrowing tales about the immediate aftermath of the attack and the longer-term consequences, in which people were dying of cancer and women were terrified of giving birth to malformed children. She has shared her A-bomb experience with world leaders and people in more than 50 countries and regions, including at the G7 Summit in May 2023.

We had a hosted dinner in the hotel, and the food was excellent—a six-course meal of Japanese specialties with a wide selection of alcoholic choices available.

Sunday, October 5 — Hiroshima

A beautiful, sunshiny day that turned hot and humid by 10 a.m. But it was a day that was devoid of WWII content. We drove about an hour to a ferry terminal for a 10-minute hop across the Seto Inland Sea to Miyajima Island. The island's most famous landmark is the Itsukushima Shrine and its vermilion torii gate, which appears to float on the water at high tide. The torii at the entrance to the shrine symbolically marks the transition from the secular world to the sacred, and a spot where kami are welcomed and thought to travel through. The shrine with its gate is honored as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The island is considered a holy place in Shintoism, with the island itself worshipped as a god.

We walked along the seaside path to reach the shrine, and Koji-san led us through the massive crowds. It was quite difficult to understand him over the radio, but I think he told a story about how the guard dog statues approaching the shrine were originally based on the Sphinx in Egypt. The Chinese refer to them as dragons or lions, but since the Japanese have no lions in the country, they choose to see them as fierce dogs. The shrine consists of wooden platforms a few feet above the water. But we were told that the water actually reaches that level from time to time. There was some sort of ceremony going on, which looked like a wedding to me, but I didn't hear the details.

We spent about 15 minutes inside the shrine, and then we had 3 hours to spend on our own. There are quite a number of tourist shops and food stands. Over 2,000 sika deer roam freely on the island, considered sacred messengers of the gods and not afraid of tourists. I brought along some crackers from breakfast to feed them, but then we were told that wasn't allowed. We were warned to keep papers and other items secured because the deer will sneak up on you and try to eat them. Two approached me right up in my face while I was sitting and reading, but I wasn't fast enough with my camera to get a good photo. They are small and pretty scruffy.

For lunch, I found a factory shop making Momiji manjū, a buckwheat and rice cake shaped like a Japanese maple leaf, a local specialty on the island. They are served warm and have a variety of sweet, gooey fillings. I got to witness a small assembly line machine that manufactures them. I also tried an agemomiji, which is a deep-fried version of the cake on a stick, this time with a cheese filling. I drank a small bottle of honey lemon soda, a local specialty made with Hiroshima lemons. Another local specialty is grilled or deep-fried oysters, but I didn't try them. Nor did I get a chance to order okonomiyaki, which is a savory Japanese fried pancake that looks similar to Egg Fu Young. It was interesting that some of these small shops have cash-fed ticket machines where you make your selection before you talk to the food server.

After ferrying back, we drove an hour to Hiroshima Castle. The castle was originally constructed in the 1590s, but much of it was dismantled in the Meiji Era, and what remained was largely destroyed by the atomic bombing. The main keep was rebuilt in 1958, a replica of the original that now serves as a museum of Hiroshima's history before WWII, and other castle buildings have been reconstructed since. The castle served as the headquarters of the 2nd General Army and Fifth Division, stationed there to deter the projected U.S. invasion of the Japanese mainland. The only thing we did was drive around the outside of the castle and look at the moat and the reconstructed tower because it is all closed for renovation.

So instead, we visited Shukkeien gardens next door, constructed as a villa in 1620 by the local feudal Lord Asano. It's a very picturesque and serene shady garden spot with a beautiful pond and lots of manicured trees. The only notable thing in the garden was an unusual stone bridge, Koko-kyo, in the shape of a rainbow. It was the only structure there that survived the bombing.

Dinner was on our own tonight, and I went to the train station where there was a remarkably large collection of bustling restaurants and grocery stores. I'm sorry to say that I got completely intimidated by all of the menus and signs written in Kanji with very few translations. Even the color photographs didn't help very much. So I ended up buying sort of a bento box with a selection of cold items that I ate in my room.

Monday, October 6 — Hiroshima and Kagoshima

We started with an "optional" morning of touring. Some people apparently wanted a morning off, so although the vast majority of us took the optional tour, there was an option to stay in the hotel and do something else for the morning. It’s ironic that one of the best military mornings of the tour was considered optional. But we all started with the requirement to have our bags ready at 7:50 a.m. for a separate shipment by truck to Kagoshima. We drove 45 minutes to the nearby small city of Kure, which was the largest naval base and shipyard in Asia during the war, the birthplace of battleship Yamato. It was a pretty scenic drive along the coast. Halsey raided here in July 45, virtually destroying the remaining Japanese navy but at the cost of over 100 lost aircraft. Eight of the flyers were taken as POWs to Hiroshima and they were killed in the bombing.

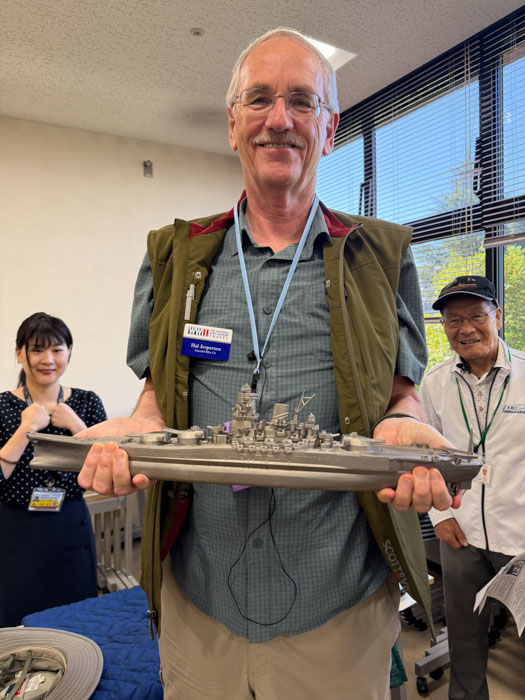

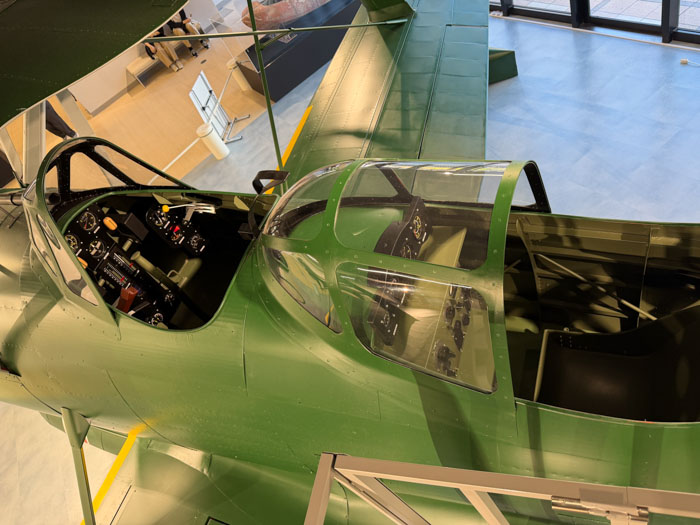

We were fortunate that Jon was on our bus today because he narrated a lot of interesting naval info about battleship construction, armor, guns, submarines, and torpedoes. We went to the Yamato Museum Satellite, a temporary small annex that is open while the main museum is being relocated. The big draw at the main museum is a 1/10th-scale Yamato, but we got to see a 1/350th-scale model instead. (I am posing below with one of these that was solid metal and must have weighed 20 pounds.) We were greeted by the museum director, Kazushige Todaka, who Jon complimented as being a noted Japanese naval historian. We had a brief PowerPoint presentation about the battleship and got to walk around a beautiful replica of a Mitsubishi F1M Zero Observation Seaplane. These were launched by catapult from Yamato to guide her long guns. Yamato and her sister ship were the largest battleships in world history, with 18.1-inch guns, but Jon noted that our Iowa-class ships had 16-inch guns with a longer caliber and were about as effective. Yamato fired her guns in anger only twice and was sunk on her way to a suicide attack at Okinawa.

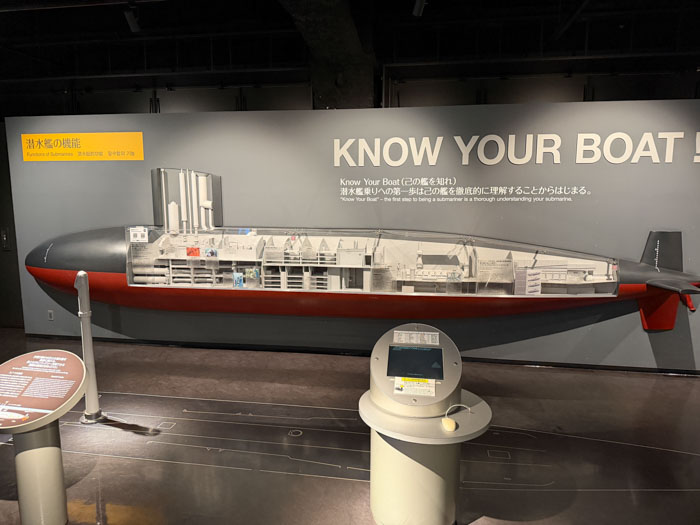

Our other stop was nearby, the Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force Kure Museum (Iron Whale Museum), which is next to the site for the new Yamato Museum. It was divided into two parts: mine clearing operations from right after the war until now, and submarine and torpedo technology. The museum is nicknamed Iron Whale because there is a large modern diesel submarine outside, Akishio SS-579, looming above the building. She was launched in 1985 and decommissioned in 2004. We walked through a small section and I very carefully avoided bonking my head!

Back at the hotel we had an hour for another buffet lunch and then we took our second Shinkansen ride, 3 hours to the southern end of Kyushu Island, Kagoshima. This train had a different seat layout. The seats were older and more comfortable than the previous trip, with only four across instead of five. We made a brief stop along the way at Kokura, which is notable to us as the secondary target for the atomic bomb on August 6th, and the primary target that was bypassed for Nagasaki on August 9th. We went directly to the Shiroyama Hotel, which is a very elegant traditional Japanese hotel sitting on a tall hill overlooking the city. We have a great view of Sakurajima, an active volcano that erupts daily with smoke and ash. The hotel offers an onsen (traditional Japanese communal bathing), but I had no interest in participating.

There was a 45-minute Q&A with Jon and James that was quite informative and productive. Any questions about World War II were in play, but most involved the Pacific theater. Jon notably had some scathing things to say about Douglas MacArthur and his defense of the Philippines and there were a number of questions and comments about the Battle of Okinawa and the proposed invasion of Kyushu. We had a hosted dinner that was excellent. Multi-course, tasty Japanese/Continental food with great service.

Tuesday, October 7 — Kagoshima

I slept poorly on a twin bed that was as hard as a rock. The breakfast buffet was about 90% Japanese, in contrast to previous hotels where the balance was more 50-50. It's a beautiful sunny day, although temperatures will approach 90 degrees. Our first stop was Sengan-en Park. It is one portion of a broadly defined UNESCO World Heritage Site dedicated to "Sites of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining." This area, once called Satsuma, was controlled by the ancient Shimadzu Clan, which grew rich and powerful maintaining trade relationships (well, smuggling) with Okinawa, the Ryukyu Islands, Formosa, and China, well before Japan was "opened" by Commodore Perry. The clan assisted in the overthrow of the Shoguns in 1867 and became part of the modern Imperial Japanese government.

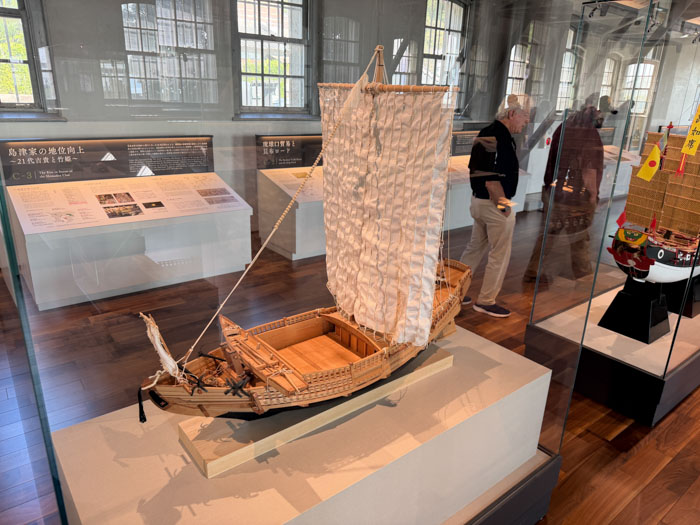

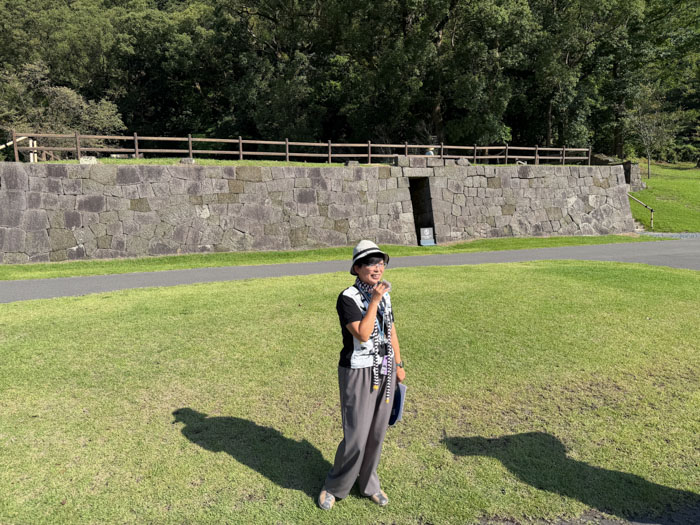

Our local guide, Mickie, led us through a nice museum about the long history of the clan. The museum is housed in the former Shuseikan machinery factory. It is amply translated, but we had to rush through and didn’t have time to read much. There are some cool ship models and a giant plaster statue of Shimadzu Nariakira, who was most influential in the industrialization and militarization of Japan and was the designer of the first Japanese national flag. We entered the garden area and saw a massive rock wall that was the Reverberatory Furnace, using techniques brought from the Netherlands to produce their first iron cannons.

We stopped at a 19th-century traditional Japanese house used by the clan. I chose not to enter because I don't feel like taking my shoes off, but the group spent about 20 minutes inside. Then, a matcha tea ceremony in which we were instructed how to mix the matcha powder and stir it into a foam with a whisk. Then, we ate a tiny sugar cat to preempt the bitter taste. (The Kagoshima variety of matcha is actually pretty mild, tasting like freshly mown grass.)

Outside the tea house ceremony was a cat shrine that had its own gift shop. Apparently, the leaders of the clan loved cats. We had 45 minutes to wander around the gardens on our own. It was actually more of a forest with rather steep hills (and at least six gift shops) than a traditional garden. On the way back, I found a sign referring to the Anglo-Satsuma War of 1863, which was an interesting overstatement. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombardment_of_Kagoshima

Our drive to lunch in Chiran was about an hour, and we started getting back into World War II content. Jon talked about Kamikaze operations and the pilots who served. As we got into the mountainous terrain, he pointed out how difficult it would be to invade Kyushu and criticized MacArthur's plans for a supposed maneuver campaign. The severity of the terrain is reminiscent of the Apennines in Italy, where the Germans kept us bottled up for months. Mickie gave us a long explanation of the various types of green tea.

As we drove into Chiran, we spotted Kaimondake (Mount Kaimon), an impressive stratovolcano in the distance. For many Kamikaze pilots, this was the last sight they saw on mainland Japan. We had a traditional lunch of many small plates in a place called Bukeyashiki. Quite good.

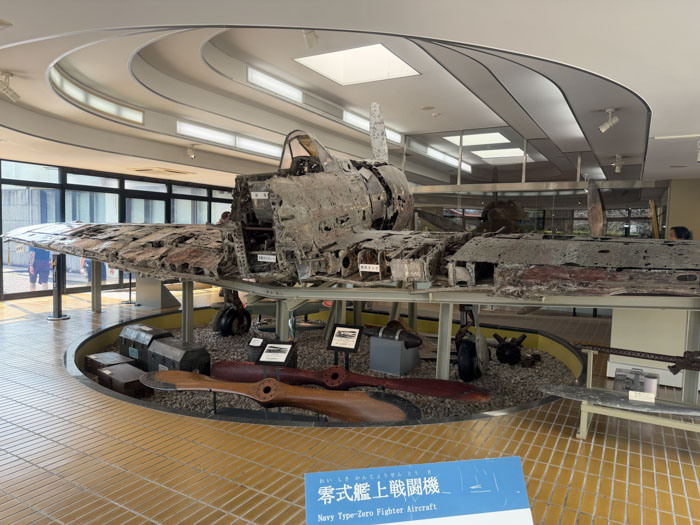

Right next door is the Chiran Peace Museum, located at the largest of Japan's Kamikaze airfields in 1945. The Japanese word for Kamikaze is Tokko. Outside is a replica of a Nakajima Ki-43 Army Type-1 Hayabusa, which the US called Oscar. Also a Fuji T-3 military trainer aircraft (from 1978). We walked by hundreds of concrete lanterns memorializing the dead pilots. Then a Shinto shrine and a “triangular house” where the pilots slept on the last few nights. From the outside, you can see through a window an original Japanese Zero fighter in very bad shape.

Inside the museum, there are 1,036 pilot photos and many mementos such as final letters home, all in Japanese, of course. But no photography is allowed inside the museum. There is a cool movie about base operations that is projected onto a 3D topographic map. There are three other movies playing that largely overlap each other, including a 30-minute movie about what goes through the heads of the pilots. Inside the no-photography zone are an actual Hayabusa and a Nakajima Ki-84 Army Type-4 Hayate (“Gale”). We spent 90 minutes in the museum and drove back to the hotel for an hour. We had James on the bus for the return and he expanded on Jon’s comments about the difficulty of Kyushu terrain.

We are on our own for dinner tonight. The hotel has a number of restaurants, but most of them require reservations, so I simply ordered a takeout pizza from the Italian restaurant in the hotel. Not bad.

Wednesday, October 8 — Kagoshima to Okinawa

This morning is an optional tour, visiting a whiskey distillery with a whiskey tasting. Since I have been avoiding alcohol recently, I declined this option. Some friends arranged a tour with a private guide to go to the volcano, and I asked to go along. We met our guide, named Kana, and took a long walk down the mountain from the hotel to follow the Samurai Trail. She frequently referred to the movie "The Last Samurai," which is a fictionalized version of some of the events that really happened here. We started at a small monument for the last samurai, and we discussed the Meiji era Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. We encountered a large statue of General Saigō Takamori, passed by the site of his final headquarters, some caves where his men hid, and finally, his death site. In his final battle, he was struck by a bullet and was mortally wounded. But before he could die, he committed seppuku. In the movie, the character representing this general was played by Ken Watanabe, and the star was Tom Cruise, a former American Civil War officer.

We walked downtown to the ferry terminal and took a 15-minute ride to Sakurajima. It was once an actual island, but now it is connected by lava to the nearby peninsula. We visited the Volcano Museum, which had a very good movie history of the volcano and the deep caldera nearby, underwater in the bay. The last really major eruption, the largest ever, was in 1914, but minor eruptions occur almost daily. The soil conditions here are very good for farming, and for some reason they have the world's largest radishes, some of which can weigh 30 kg. We considered taking a bus up to the observation point about halfway up the mountain but decided against it for reasons of time. One of our group was interested in doing a hot springs foot bath, but it didn't entice me. She reported that the water was probably 120 degrees, and you could only put your foot in for a second.

We took the ferry back to downtown and a taxi back to the hotel, where we met the rest of our group for lunch, another Japanese buffet. Then James gave us a presentation on Japanese Airborne Operations in 1942. He described the differences between Army and Navy paratrooper equipment and then three battles in the Dutch East Indies: Manado on Celebes/Sulawesi, Palembang on Sumatra, and Koepang on Timor (a Navy drop). The airport was about 45 minutes away. We flew 90 minutes on an airline I hadn’t heard of previously—Solaseed (code-shared by ANA). We met our guide for the remainder of the week, Hayato, and arrived at the Hyatt Regency Naha hotel about 8:15 p.m. Since there was little time for a formal dinner, we were given bento box meals to eat in our rooms. It was quite a large portion of very good cold Japanese food. Some of the younger and more enthusiastic tour participants decided to rush out and go downtown, only a couple of blocks away, for restaurant Japanese food.

Thursday, October 9 — Okinawa

A hot day is in store, up to 90°, but it's a good day because we will be immersed in World War II content, Operation Iceburg. Residents of Okinawa referred to this battle as a "typhoon of steel." We drove north, and still within the city, we passed by two very low hills, Sugarloaf and Half Moon, which US forces attacked for over two and a half weeks before defeating them. There was a tunnel connecting them underneath that we did not know about at the time. As we proceeded up about two-thirds of the island, John described the campaign at a high level and talked about the massive amounts of artillery that were expended against the island. He talked about the Japanese command structure and how the subordinate Lt. Gen. Isamu Chō was an aggressive infantry officer who wanted to counterattack. He eventually convinced his commander, General Mitsuru Ushijima, resulting in attacks April 12–14 with about 5,000 Japanese lives lost. Jon said that there was a problem in the Japanese army that some junior officers were rather rebellious, with insubordination that they called "command from below." He talked about the friction between the Okinawans and the Imperial Japanese Army, which had very little regard for the lives of civilians.

I asked Hayato about current US forces, and he said they occupy about 20% of the land area here. He actually works at Kadena Air Force Base as an HR manager. His English is so good because he was an exchange student at a high school in Denver. We stopped at Yellow Beach, which is where the 7th Infantry Division landed, one of four divisions landing on a 16-kilometer front, the Hagushi beaches. There is a very modest Okinawan-erected monument on a small hill overlooking the area. We walked on the beach where the actual landings occurred on April 1st. One of the members of the tour had an ancestor here, and he informed us that this area was used as one of two staging grounds for Higgins boats that were intended for the invasion of Kyushu.

Our next stop was the Chibichiri Gama (Cave), where 140 civilians hid from the approaching American troops; they had been warned by the Japanese army that if captured they would be raped and killed. Two men and one 18-year-old girl emerged from the caves with bamboo spears and attempted to attack the US soldiers, but they were wounded and returned to the cave. Panicking, 83 of the civilians committed suicide. It was not possible to enter the cave, and we were warned repeatedly about mosquitoes and snake bites. At nearby Shimuku Cave, which we did not visit, two Okinawans who had worked in Hawaii convinced those civilians that they would not be harmed, and they emerged to join the Americans.

We had a buffet lunch at Hotel Nikko Alivilla. It was quite bountiful and included the best sushi and dumplings we’ve had on the trip, along with dozens of other mostly Japanese choices. Next was an hour to Kakazu Ridge, the first defensive perimeter in what would be called the Shuri Line. On the way, Hayato related the story of his grandmother’s experience in a cave. She was lucky enough to believe two American soldiers who promised them food and no harm. He also outlined the history of Okinawa and explained about blue zones where longevity is highest. The U.S. threw three divisions successively at Kakazu Ridge from April 8 through April 21.

We went through a modern park and walked 120 steps up the reverse slope of the ridge, which is actually two hills with a connecting saddle. The front of the ridge is really steep, reminiscent of Missionary Ridge in Chattanooga. In the distance, we could see a Marine Corps Air Station that is controversially nestled inside a residential area. Some V-22 Ospreys flew over us as we were visiting the ridge. Many of the Japanese defenders hid in fortified caves. There is a pillbox that the Japanese called Tochka, and some of the members of our tour were able to crawl inside a tiny hole to get into it. John described the most damaging tank battle in the Pacific War in which 30 tanks of the 193rd Tank Battalion attacked on April 18th, and 22 of the tanks were destroyed or disabled by Japanese mines and anti-tank guns.

We drove to nearby Hacksaw Ridge. I was disappointed to learn that the hike up the ridge was very strenuous, with a lot of steep steps that had poor handrails. Jon discouraged anyone intimidated by this from going, so I reluctantly stayed on the bus. (As I get older, I am increasingly nervous going down shallow stairs without a good handrail. However, I was further disappointed to find out from the people who took the hike that it was not nearly as strenuous as advertised.) There is a small admin center/museum.

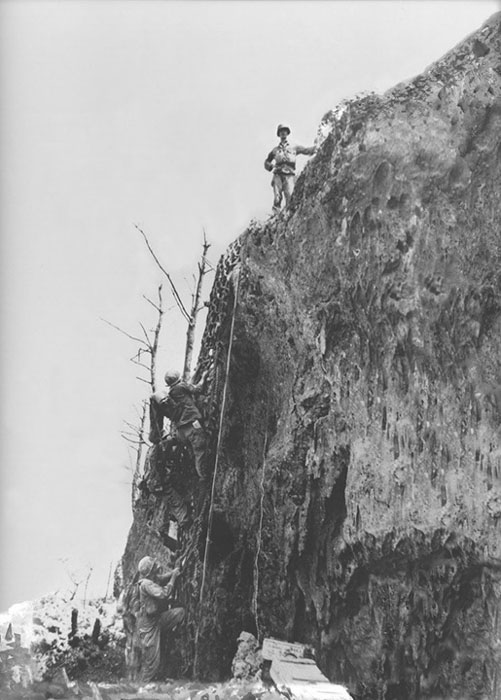

The Maeda Escarpment, also known as Hacksaw Ridge, is a 500-foot-high plateau that stretches approximately 4,200 yards from east to west. Its face is a sheer rock wall that could only be scaled with ladders or specialized climbing equipment. The entire mass was covered in narrow, jagged ribbons of rock, completely surrounded by Japanese guns. Unbeknownst to the Americans, Hacksaw Ridge was heavily fortified as the second line of defense after Kakazu. Within the ridge, there was a vast cave system, some of which were large enough to accommodate hundreds of men simultaneously. Passageways connected these caves to each other and to the top of the ridge, where hidden gun ports could unleash a barrage of fire on attackers.

From April 25th to 29th, the 96th Infantry Division burned itself out assaulting this position. The 77th Infantry Division took up the fight and by early May had essentially encircled the position. During this battle, medic Desmond Doss, a conscientious objector, performed extraordinary feats of valor on May 2–5, single-handedly rescuing 75 wounded men from the clifftop under heavy fire, treating injuries, and lowering them via ropes—actions that later earned him the Medal of Honor, despite his own severe wounds. (This is the subject of the excellent film Hacksaw Ridge.) The Japanese ordered a two-division counterattack on May 4th, but it was repulsed by the Americans.

Our final stop of the day was the ruins of Shuri Castle, the headquarters of Gen. Ushijima’s 32nd Army, and which gave its name to the Shuri defense line. Beginning on May 25th, the battleship USS Mississippi shelled it for three days, obliterating it. It was destroyed again in a fire in 2019; reconstruction is underway. We stopped outside the army HQ entrance and saw a map of the extensive tunnel network through the complex. The castle grounds are a large park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Hayato pointed out that while most Japanese castles were created to protect the shōgun inside, this one was created to protect sacred areas, such as a large tree and bush. There's not much to see except for an observation platform that allows you to view almost half of the entire island from the landing beaches down to the final battle on the southern end. Unfortunately, it was so overcast and hazy from a passing storm that we couldn't really see very much.

On the way back to the hotel, Ayato gave us a lot of information about Okinawa culture and the economy. Among a number of statistics, he said that 86% of the economy is based on tourism. I asked him why people come here. Is it to the beach? He said he did not know why anybody came to Okinawa, except that a lot of Chinese come to shop. We had dinner on our own tonight, and I couldn't find anyone to eat with, so I did another convenience store run and had fried chicken and rice balls in my room.

Friday, October 10 — Okinawa

It’s cooler today because of some passing showers. James gave us a bus talk about US Army division organization and told us that because of the intensity of fighting along the Shuri line, five divisions lined up with all their regiments up front, no reserves in the rear. Then he described the evacuation of the Shuri line. We arrived at Japanese Naval Headquarters, which was a series of tunnels stretching 450 yards underground; 300 yards of these tunnels are currently open for visiting. There are various rooms to peer in, such as a command center and a signal room. Navigating through the tunnels was a challenge for a tall guy, but I am proud to say I did not bonk my head even once. The amazing thing about these tunnels was that 4,000 guys were down in here without any bathrooms or beds, so it must have been even more miserable than the average military situation. It was here on June 13 that Rear Admiral Minoru Ōta committed suicide after writing a famous letter to officials in Japan, lauding the Okinawans’ participation in the battle and recommending that they be treated well in the future. There is also a small museum.

Back on the bus, James described the US blowtorch and corkscrew tactics. The former was the use of Sherman tanks with flamethrowers, and I did not quite catch what the corkscrews were supposed to be, but it all involved flushing soldiers and civilians out of caves.

We drove to the General Buckner Memorial, which is up a hill and reached by a steep staircase that has no handrails, so I did not feel comfortable going up (or, rather, down). The pictures I have below are from the Internet. Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., the son of the Confederate general who surrendered to Ulysses Grant at Fort Donelson (unconditional surrender), was killed by Japanese artillery fire on this spot and was the highest-ranking American general to die from enemy fire in the war.

We had another buffet lunch at Southern Beach Hotel, pretty good but not as good as yesterday. A giant downpour came through while we were eating. Then the Himeyuri Peace Memorial, which was the final Japanese field hospital for the campaign. The focus of the museum was on the girls in the Himeyuri school. All young students were drafted into service, and the girls were ordered to become nurses. They fed and ministered to wounded Japanese in the tunnels under extreme circumstances, but the worst came on June 18th, when the Japanese army started to retreat and they received a deactivation order. The military essentially told them to get out, and they were set loose right in the middle of the battlefield without any protection. The museum was very nicely done with good bilingual exhibits, but no photographs were allowed. There's an interesting diorama of activities in one of the caves, and the exhibits have numerous excellently drawn maps. Outside there is a monument that contains the remains of 136 students.

Our final stop of the tour was the Okinawa Peace Memorial Museum, which is a large complex of a museum and memorial grounds. There are marble markers with the names of 242,000 killed in the battle, including 14,000 Americans. The World War II Museum provided a wreath to be laid at the feet at one of the American markers. This area overlooks the sea at the Suicide Cliffs, where thousands of Okinawans threw themselves and sometimes their children to their deaths to avoid capture by the evil Americans. Inside the large, modern museum there is an excellent movie about the campaign with an impressive 3D map of the island. And an even bigger set of cave dioramas. There is an extensive section on recovery after the battle, the American occupation and the reversion to Japan in 1972. But once again, no photos were allowed.

We walked up Mabuni Hill and passed by numerous monuments to those fallen in the war, erected by various prefectures. I asked about why there isn’t something similar in Tokyo and was told that there isn’t enough land available. At the very peak of the hill is a monument remembering the suicide of Gen. Ushijima there, which marked the end of the Japanese defense. On the bus return trip, James discussed the idea of an amphibious end run to the south end of the island, which was rejected by Buckner, who feared a situation like Anzio.

There was a farewell dinner, yet another hotel buffet.

Saturday, October 11 — Flying Home

The museum provided a ride to the airport. I have a couple of difficult travel days ahead: Flying home via Seoul with a 6-hour layover and a direct flight to San Francisco on Asiana Airlines. Then I have about 20 hours to rest up, launder my clothes, and repack my bags before flying to Rome for a tour of the Italian Campaign, Salerno to Florence. My travelogue for that trip is here.