Hal Jespersen's World War II Italian Campaign Tour, October 2025 [Part 1]

This is my (Hal's) report on a trip to examine the World War II Italian campaign sponsored by Valor Tours. This is my fourth tour with Valor and the second in which I am visiting Italy for WWII. The first trip to Italy was with Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours, but I was not fully satisfied with the amount of military content on that tour. So I am returning to Italy with a well-known expert on the campaign, Frank de Planta. I toured with Frank last year in France for the 80th anniversary of Operation Dragoon, and thought he did a fantastic job.

Since I took a lot of good photographs on the Ambrose trip in different weather conditions, I have included some of them in this report identified with "[2022]."

This is a lengthy report with a lot of photographs, so I have divided it into two parts:

Contents – Part 1

Sunday/Monday, October 12/13 — To Rome and Salerno

This is a challenging travel weekend for me because just yesterday I returned from Okinawa, Japan, after completing a tour with the National WWII Museum. So that's about 24 hours of combined flying time and a 17-hour time difference. (If I had planned these two trips at the same time, I might have flown directly from Japan to Italy. But they were separate bookings, and I wanted to get home [if only for less than a day] to see my wife Nancy, do my laundry, etc.)

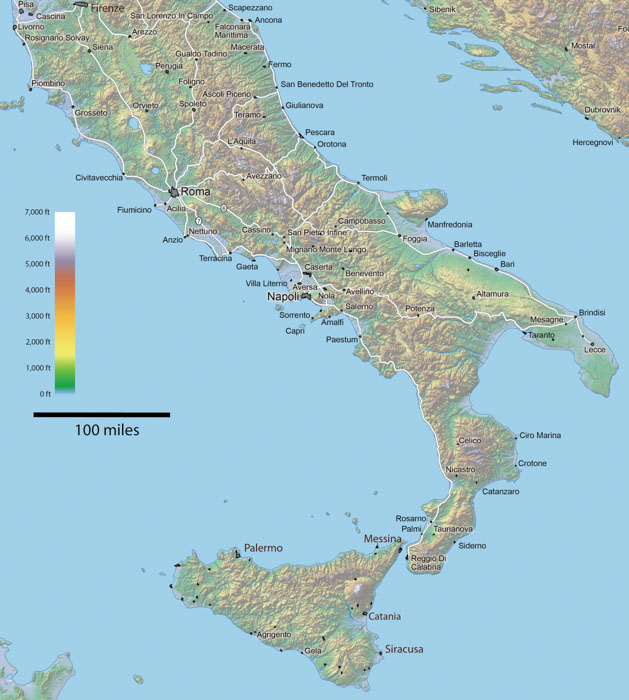

Sunday late afternoon, I flew United Airlines directly from San Francisco to Rome’s Leonardo da Vinci–Fiumicino Airport (FCO), arriving early afternoon on Monday. The flight was comfortable, and the weather flying down the Tyrrhenian Sea coast was gorgeous. I took a number of photos upon my departure from the San Francisco Bay Area. The European Union has established a new entry-exit system for visitors, which went into effect yesterday. At border control, they had started using it at least partially (no fingerprints yet), and there was a line of about 200 people waiting to access the cameras and passport scanning machines. Fortunately, it moved along quickly, but there still had to be a human agent stamping the passports manually.

Frank picked me up in his rented Volkswagen, and I met the other tour guest, a doctor from Pittsburgh named Gus. I have to assume that Valor is losing money on this tour with only two paying guests. Frank gave us our map and information books, which were over 250 pages, many in color, so I knew that we were in for a very detailed military experience. We drove a little over three hours to get to the Salerno area. We took the Autostrada that paralleled historic Route 6 down through the Liri Valley, and Frank gave us a running commentary on all of the terrain we passed by, an advanced look at what we will see in the coming days as we follow the course of the Army in the reverse direction. He pointed out a few hilltop villages, situated on those hilltops to avoid the malaria that was prevalent in the valleys. He described how the Germans would have a single artillery field observer calling in fire from all over, and the army had to assault each town to neutralize this. We checked into the Palace Hotel in the town of Battipaglia, quite a modest property. Dinner was in the hotel restaurant, which did not open for service until 8 p.m., challenging my jet lag a bit. I had Pasta e Fagioli in Bianco and then Bocconcini wrapped in thinly sliced ham. Quite good. (All breakfasts and dinners are included as part of the tour.)

Tuesday, October 14 — Salerno

It's a beautiful sunny day today except for some hazy conditions. Our first stop was the British Cemetery in Salerno. An interesting internee is the great-grandson of the Duke of Wellington of Waterloo fame. There are almost 2000 graves in the cemetery. We drove to Castello di Arechi to get a spectacular view of the entire Bay of Salerno. Frank went into detail about the plan for Operation Avalanche, the invasion of Salerno. Two corps assaulted the invasion beaches: the Tenth British Corps, which consisted of two divisions, and the U.S. VI Corps, which had only one, the 36th Infantry Division. Frank is a critic of Lt. Gen. Mark Clark and outlined two really bad initial decisions the general made. First, he wanted to invade as a tactical surprise, so he did not allow naval gunfire prior to hitting the beach; the British Corps commander ignored this requirement and did use naval gunfire, but the Americans went in without support. Second, he instructed the U.S. corps to board the landing craft 14 miles away from the beach, whereas the British once again ignored him and boarded at 4 miles. Thus, the British were able to expand their beachhead much more quickly than the Americans did. Well, actually, there was a third bad decision, and that was to send the American corps in without any artillery at first.

We drove down to the beach in Paestum to see where the 36th Infantry Division came ashore. I believe it was the Yellow Beach. The initial plan was to expand the beachhead to be about 100 square miles on the first day, but neither the British nor the Americans came anywhere close to that. Just inland is a modest monument to the 36th ID. (When I visited this area in 2022 with Stephen Ambrose, we coincidentally got to meet the local resident who built the monument. We also spent a few hours visiting the Grecian ruins at Paestum.) Also inland is a tall tower built by the Romans 2,000 years ago that was used by the Germans as an observation post and machine gun emplacement.

We drove by Clark's headquarters, which was a tobacco drying warehouse, but did not stop for a visit or photos. Our next stop was Hill 386, where we parked outside of a monastery just below the peak and got a dramatic view of most of the American sector of the battlefield. Frank related how the 142nd Infantry was split into pieces to take a variety of objectives in different directions. Then we found a small café for lunch, and I had a very nice Amatriciana pasta dish.

Next was Hill 424 above Altavilla, the key vital terrain of the entire battle. The 1st Battalion of the 142nd drove the Germans off and occupied it. But they should have sent an entire brigade because that battalion was easily picked off by a German counterattack. We saw how the German control of this hill and the town of Eboli on the other side of the wide valley spelled disaster for the 179th Infantry that tried to move through the valley. Frank described how on September 13th, the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division arrived from southern Italy and almost turned the tide of battle. We next visited the area of the famous Burned Bridge, in which elements of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division and the 16th Panzer Division were traveling down the road constrained by two parallel rivers, and they encountered two American Field Artillery battalions (189th and 158th) that used their 155mm howitzers as anti-tank weapons to stop the advance.

We visited the tobacco factory where the 1/157th Infantry fought on September 13th. Only a portion of the circular collection of buildings remains. Then we left the area and started heading north. We drove through San Severino Pass and crossed the Volturno River, where German delaying tactics caused fighting for about a week. We left the autostrada and changed over to State Route SS 6, which was the significant road during the war. We drove up Monte Lungo and had a great view of the Mignano Gap, then crossed the valley and climbed up to San Pietro Infine. It was part of the German Bernhardt Line (Winter Line) and overlooks the Liri Valley from the foothills of Mount Sammucro. The 36th Infantry Division fought a grueling battle here in mid-December against the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division and a battalion from the 71st Infantry Division losing about 2,000 killed. The original town was completely destroyed in the war and was rebuilt lower down the hill. There is a small museum here that documents the woes of the residents of the town, but it was closed today, as it is usually. There is a church at the top of a steep hill that we did not climb to visit. This battle was the subject of a John Houston film, The Battle of San Pietro.

We drove to the town of Cassino and checked into the Hotel Rocco, a Best Western-branded property, where we will stay for the next few nights. It's a couple of kilometers outside of downtown Cassino, which is not much of a problem because the town isn't very interesting. It happens that this is the hotel I stayed in during the Ambrose tour in 2022. Dinner in the hotel restaurant was pretty good: a spaghetti cacio e pepe and a swordfish main course.

Wednesday, October 15 — Monte Cassino, January Battles

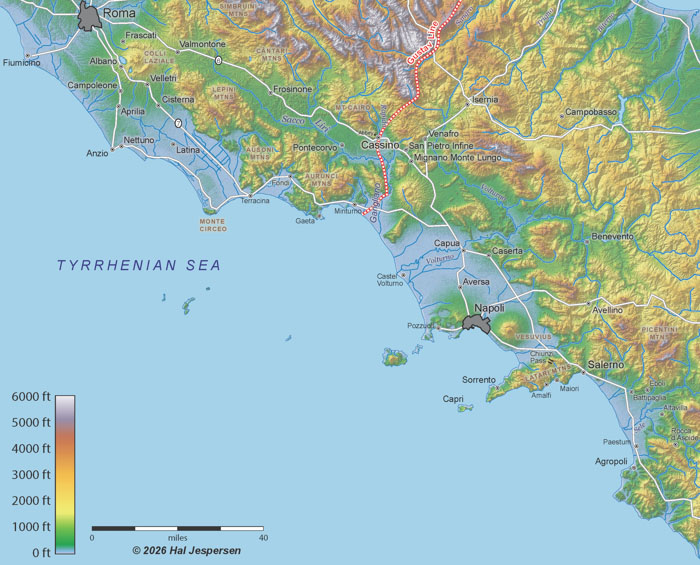

The weather has turned a little chillier and overcast. We started at an intersection that the GIs called Shit Corner. Frank led us through a detailed orientation to the surrounding terrain. He described the January attacks in this area as being piecemeal attempts by the Fifth Army that happened every couple of days between January 12th and 20th. We would spend the rest of the day going into these attacks in detail.

We drove about twelve miles west toward the sea, near the towns of Castelforte and Maiano, where the British Tenth Corps fought to break through to the Ausonio Valley. Frank was very critical of Mark Clark's decision to take the 46th Division away from General McCreary's corps for his planned attack at St. Ambrogio. Without the 46th, the British had only two divisions, the 56th and 5th, and no reserve to provide momentum after an initial breakthrough could be achieved. We drove up Mount Damiano and had a great view of the village of Castelforte. Then we traveled around the mountain to the town of Ventosa, where we got a clear view of the Ausonio Valley. We heard of the advantages of the valley, which would offer a direct connection to the Liri Valley and the road to Rome. This point was the farthest advance that the British made in January.

Then we proceeded farther west to view the coastline and discuss the attacks by the 5th British Division. Along the way, Frank described a tour he gave for the benefit of Kit Harington, the actor who played Jon Snow on Game of Thrones, who had an ancestor that fought in this battle. He revealed that today is his 241st visit to Monte Cassino. The terrain in this area consisted of two hills with Ausonio Valley in between. On the right (east) was Mount Damiano, and on the left was a lower hill that hosted the towns of Tufo, Minturno, and Tremensuoli. The latter was the 5th Division's objective. The entire line was protected by the Germans’ Gustav line of fortifications. In Minturno, we got a good view of the coast and a small fortified hill called Monte Argento.

An interesting part of this battle was a minor amphibious assault. The Second Royal Scots Fusiliers and a couple of additional companies took amphibious ducks (DUKWs) to bypass the Garigliano River. Unfortunately, the American duck drivers landed them in the wrong spot, short of the river. The Scots advanced, firing, into the ongoing attack of English forces heading toward the smaller hill. They went back to the coast, re-boarded the ducks, and were finally landed in the correct spot. The remaining British units crossed the river and advanced against the lower hill but were unsuccessful in seizing it. Frank reiterated that the loss of the 46th Division by Mark Clark's diktat could have made the difference in this battle. We climbed Monte Natale and had a great view of the Ausonio Valley, which would have been opened up if the Tenth Corps attack had been successful.

We drove down near the mouth of the Garigliano River to visit the Minturno British Cemetery, which inters about two thousand British soldiers, mostly from this area of the battle. Frank recounted the history of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, founded by Fabian Ware, a World War I ambulance driver who was eventually promoted to Major General. We heard a lot of details about the architecture of most of the British cemeteries and the practices for marking the gravestones. We visited the grave of C.A. Mitchell, a Victoria Cross recipient, and heard the citation describing his heroic exploits, taking out multiple machine gun nests, mostly by himself.

We drove back to Cassino via the Ausonio Valley and had a lunch at Forno Lanni Panaficio, a small bakery. I had two pieces of pizza that were scissored out of a large sheet pan, "al taglio” style, and it was quite good, a perfect lunch for me. (We ate at this same place all three days in Cassino.) We spent the afternoon examining the disastrous attempts to cross the Rapido River by the 36th Infantry Division, January 20–22. We stopped at a sheep ranch north of the town of Sant’ Angelo and were amused by the local sheep dog who barked nonstop at us for about 30 minutes. This whole battle was screwed up throughout, mostly due to the incompetence of Mark Clark. The invasion of Anzio was imminent, and Clark wanted to reduce the German threat in that area by luring more German forces down to the Monte Cassino area. This is ironic because the whole point of the Anzio invasion was to distract the Germans from Monte Cassino.

Fred Walker's division of Texans attacked with two regiments, the 141st and 143rd, north and south of Sant’ Angelo, respectively. The attack consisted of men hand-carrying boats that weighed 1500 pounds downhill through a minefield that had been cleared in narrow lanes and then up over a berm, and down a rather steep riverbank. (It was actually the Gari River, but the GIs mistakenly called it the Rapido, which was a nearby tributary of the Garigliano.) A preliminary artillery bombardment across the river was ineffective, and the regiments made zero progress reaching beyond the far bank. Clark ordered a second attack, which Walker was able to delay until dark. But that too was repulsed with ease by the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. A third attack was ordered, but Clark eventually changed his mind. The Texans lost 1,961 men killed in this fiasco, the Germans 64. The survivors petitioned U.S. Congress to open an inquiry into this battle, and although the U.S. House of Representatives failed to formally accuse Clark of wrongdoing, his Army career was marred in the 1950s because of this disaster.

We visited the town of Sant’ Angelo and saw a monument to the 36th Infantry Division. Then we finished up mid-afternoon to get some rest from a long day. We had dinner in the hotel again. I had a Rigatoni Carbonara and meatballs in tomato sauce. Pretty good.

Thursday, October 16 — Monte Cassino, February Battles

Today we are continuing with the late January-early February battles that are considered by most historians to be the first battle of Cassino. Mark Clark and the official history by the U.S. Army Green Book consider the first battle of Cassino to be those on the Winter Line, including San Pietro. We drove north on the Caruso Road to Caira, passing by the former barracks building and jail. There we visited the German cemetery that intersected about 22,000 soldiers who fell from here all the way to the southern end of the Italian boot. They are buried six to a grave marker. I visited here in 2022, but I have noticed new and improved signs, and there is now a brief video in the museum that provides the timeline of World War II in Europe.

We drove east into the mountains and reached about halfway to the city of Vanefro. The 34th Infantry Division was there when they were given orders by Mark Clark to attack Cassino. Rather than traverse the entire 30 kilometers, we concentrated on the logistical details of that movement. Over two and a half days, Army engineers blasted a rough road across the mountains called the Inferno Track. We stopped in the area called the Hove Dump that had been established as a supply point for the Indian divisions in the campaign. We also learned about the Cavendish Road that was created to supply Polish troops. Constructed in 10 days, it connected the village of Caira to Snakehead Ridge.

We then discussed the January 25th attack by II Corps units, including the 34th Infantry Division. After traversing the Inferno track, the 34th launched the ordered attack with three regiments. The 133rd Infantry, reinforced by a tank battalion, was ordered to attack the village of Caira. The 135th, also with a tank battalion, was intended to turn left and travel around the base of the monastery mountain and head into the Liri Valley. The 168th was held in reserve. The 133rd attack was repulsed, so the 135th changed directions and attempted to perform the same attack right behind it. But it was unsuccessful, so nothing was accomplished.

We then moved ahead to the second battle of Cassino, Operation Avenger, February 15–20. Mark Clark wanted to pressure the Germans at Cassino in order to alleviate threats to the newly established Anzio beachhead. (Spoiler alert: it did not prompt any German relocations.) Newly arrived on the battlefield was Lt. Gen. Sir Bernard Freyberg, a New Zealander, who was assigned to command a newly formed corps consisting of the 2nd New Zealand Division and the 4th Indian Division. (Clark was offended that Alexander had sent these additional troops, considering it to be an insult implying that he could not get the job done with his own men. He did not provide the resources for Freyberg to establish a true corps headquarters, so the New Zealanders' staff served both the division and the new corps.) Freyberg became convinced that the Germans were occupying the Benedictine monastery with artillery observers, so he politicked with the New Zealand Prime Minister and Winston Churchill to force a bombing mission on the monastery. On the 15th, the U.S. Air Force dropped 576 tons of bombs on the Benedictine monastery, obliterating it. Besides receiving worldwide condemnation for destroying a historic religious installation, it was also fruitless. The Germans had not in fact used it as an artillery observation platform, but with its destruction they occupied the ruins.

There were two parts of the second battle, which Freyberg envisioned as a great pincer movement. In the first, the New Zealand division was to attack the railroad station in Cassino. But because of flooding conditions, they were only able to traverse the area on a railroad bed, which limited the number of troops they could use, and they ended up with an attack by only two companies of their Māori battalion. They reached the station but were surrounded by the 1st Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) Division, and the attack failed. We discussed this attack while about three-quarters of the way up Monastery Mountain, and did not visit the railroad station. The second part was a series of attacks on the Monastery and Snakehead Ridge’s Hill 593, by the Indian division. All failed with severe losses. One company of the Royal Sussex Regiment attacked Hill 593, and none of the soldiers or officers came back. We drove up Snakehead Ridge to see the terrain on a narrow and severely potholed road built by the Poles. We heard stories about the severe conditions for the wounded who sometimes had to wait all day before they were evacuated. We visited the doctor's house where the initial triage was performed. It is now a farm owned by a man who has chickens and sheep, leading a solitary lifestyle on the mountain.

We drove over to the monastery and had a relatively short visit. Unlike my trip with Ambrose in 2022, today we did not take a guided tour or spend any attention on the religious aspects of the building. Then we drove downtown for a delicious dish of gelato. Dinner at the hotel was an unfamiliar pasta with tangy cheese and a chicken breast with orange sauce.

Friday, October 17 — Monte Cassino, March and May Battles

Today we will be covering the fruitless third battle of March 1944 (Operation Dickens) and the very successful fourth battle (Operation Diadem) in May. As we approached the road up to Monastery Hill, we passed the blockhouses used by the Germans, called the Hotel of Roses and the Hotel Continental. We stopped on the road about halfway up the hill to get a view of the castle on Hill 193, which was captured by an Indian battalion and then taken back by the Germans and then captured again. From our elevated position, we talked about the New Zealand Division’s movement on Caruso Road around the base of the mountain.

General Freyberg was back again with a plan for Dickens. Once again, he ordered a strategic bombing raid, this time against a square mile of downtown Cassino. The Air Force dropped 1,112 tons of bombs on March 15th, and 200,000 rounds of 155mm artillery struck the area, turning it into ruins, which unfortunately for our side made it impossible to use armor within the city. Freyberg's plan called for the 4th Indian Division to attack the monastery and the 2nd New Zealand Division to attack inside Cassino, and it was critical that both of these attacks be launched simultaneously so that they were not defeated in detail.

Despite a near-successful assault by New Zealand forces on the 15th, a delayed follow-up attack that evening failed due to German reorganization of defenses and unexpected heavy rain, which flooded craters, turned rubble into mud, disrupted radio communications, and obscured moonlight needed for clearing routes through the ruins. On the right flank, New Zealand troops captured Castle Hill and Hill 165, allowing elements of the Indian 4th Infantry Division to advance; in the ensuing confusion, the 1/9th Gurkha Rifles seized Hangman’s Hill (Hill 435), while the 1/6th Rajputana Rifles’ assault on Hill 236 was repelled. By the end of the 17th, the Gurkhas held Hangman’s Hill in battalion strength just 250 yards from the monastery, though their supply lines were vulnerable to German positions; meanwhile, New Zealand units and armor pushed through to capture the railroad station.

We traveled to the Polish cemetery, constructed on the side of Hill 593. Frank told us the history of the Second Polish Corps. After the fall of Poland, the Soviets removed a million and a half people to labor camps. They were eventually released and through great personal hardship migrated across Russia to Iran, to Mosul in northern Iraq, to Gaza, and then finally to join British forces in Italy. Their general, Władysław Anders, was an inspirational figure and was able to keep the soldiers loyal to the Allies even when Poland was betrayed at Yalta. They had visceral hatred for both the Germans and the Russians, and once trained and equipped, they were fierce and effective fighters. The cemetery is the home to 1,051 Poles and is an extremely popular tourist attraction for the Polish people. There were five large busloads coming in as we visited the cemetery. Some of them participated in religious services on the grounds, and others sang patriotic songs. There is a small museum that has been opened recently, and it is quite well done, describing the history of the Poles in the war.

We drove up the hill on the same bumpy road as yesterday and stopped at the Albaneta farm, which during the battles was a German aid station and is now the home to a brewery owned by the monastery. Here we discussed a diversionary attack that was launched in conjunction with the Indian and New Zealand attacks. On March 19th, 15 Sherman tanks and some Stuart light tanks of C Squadron, 20th New Zealand Armored Regiment, drove up the Cavendish Road and reached this point, achieving complete surprise. Unbelievably, they were not accompanied by infantry. So there was nothing they could do when German soldiers started surrendering to them, and they eventually withdrew having no effect. We visited a Polish tank monument that consisted of a Sherman that had been damaged by a landmine with its turret blown off.

The action with the damaged tank occurred in the fourth battle in May, when Hills 593 and 575 were attacked successfully by two Polish divisions. Frank described the plan for Operation Diadem. This was the first battle that involved more than the U.S. Fifth Army. Alexander brought in elements from the British Eighth Army and was in overall command; Clark was responsible for attacks near the coast as well as the Anzio beachhead breakout. The plan had three objectives: destroy the right wing of the German 10th Army; push the German 14th Army behind the Tiber River; advance quickly to the Gothic Line, aiming to reach it before it could be reinforced by the retreating Germans. Unlike the relatively weak attacks in the first three battles, this one featured 21 allied divisions with 12 of them forward in the attack, nine of them in reserve.

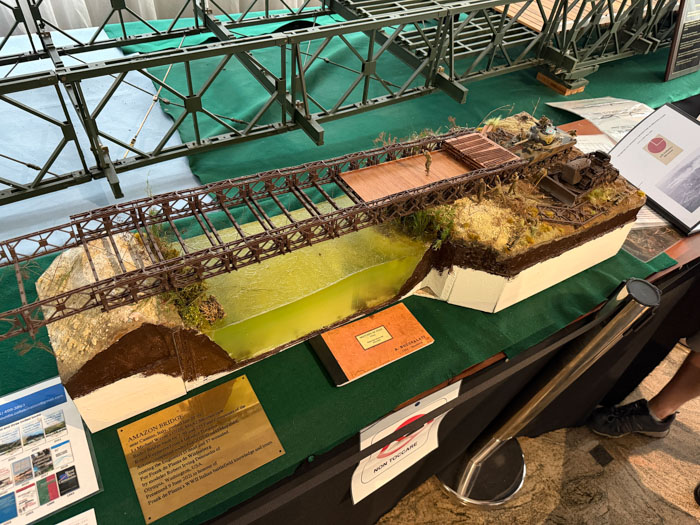

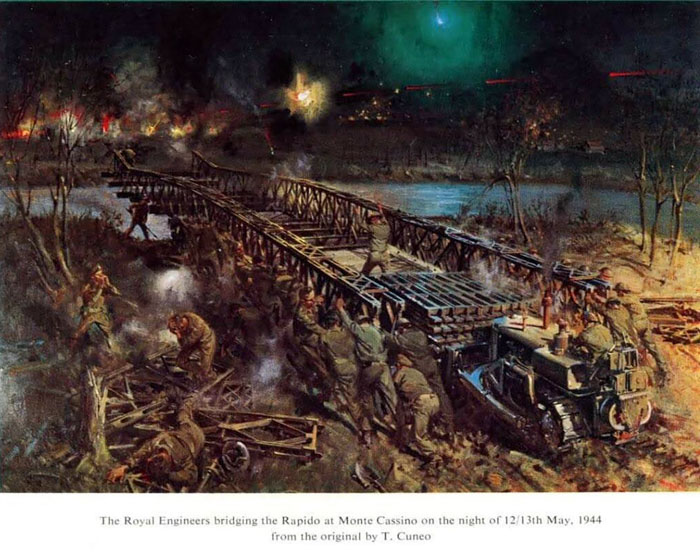

We lunched again at the bakery and then drove to La Pieta, where we viewed the Gari River and its three crossing points named Congo, Blackwater, and Amazon. This was roughly the same area as used by the 36th Infantry Division, but instead of regiments crossing, here we had divisions. There were three British bridging companies, but the Royal Engineers commander decided to focus entirely on the Amazon bridge to start. It took successive work by the three companies under fierce German fire for twelve hours to eventually get the 80-foot bridge across. The final operation to push the bridge to its completed position was held up because the engineer bulldozer broke down. So they fetched a Sherman tank to push it into position. There is an intricate diorama in our hotel that depicts this action. An American friend of Frank's, Bob Disourdis, created the diorama to Frank's specifications. Bob also did a really fantastic Sherman model, which was probably about 1/7th scale to match a training model Bailey Bridge that Frank rescued from the UK engineering school.

The Fourth Battle of Monte Cassino began on May 11, 1944, at 23:00 with over 1,600 artillery guns from the U.S. Fifth and British Eighth Armies bombarding German positions along the Gustav Line. Allied advances commenced within two hours, but progress varied on May 12: the U.S. II Corps faced stiff resistance along the coast and Route 7, while the French Expeditionary Corps (FEC) advanced effectively into the Aurunci and Lepini Mountains, linking with the British. The British XIII Corps crossed the Garigliano River, establishing a bridgehead that allowed Canadian armor to engage. Meanwhile, the Polish II Corps endured fierce fighting on Snakeshead Ridge against the 4th Fallschirmjäger, repeatedly assaulting Hill 593 over three days and suffering nearly 3,900 casualties before halting their efforts.

By May 13, the U.S. Fifth Army pushed back defenders on the coast, the FEC captured Monte Maio and supported the British advance up Route 6 in the Liri Valley, prompting Kesselring to commit reserves to hold a retreat route to the Hitler Line. Over the following days, Allied forces made steady gains, aided by daring night attacks from Moroccan Goumiers in the mountains, which Mark Clark praised as a brilliant advance key to reaching Rome. On May 15, the British 78th Infantry Division reinforced by isolating Cassino, sealing German retreat options. After a renewed Polish assault amid heavy bombardment, Kesselring ordered withdrawal on the night of May 17; by May 18, Polish troops linked with British forces in the Liri Valley, marking the collapse of the Gustav Line.

We drove on Route 6, around the mountain, and headed into the Liri Valley. We saw first-hand how dominating Hill 593, the vital terrain of the region, is on this valley headed to Rome. The remainder of our day focused on the continuation of the attack against the Germans who had retreated to the Hitler Line, which stretched between Aquino and Pontecorvo. We stopped at an elevated point in Piedimonte to get a view of the applicable terrain. Then we stopped at some farmland near Aquino to examine in tactical detail the attack of the 2nd Canadian Brigade against the line. The PPCLI (Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry) Regiment suffered severe casualties on this ground traversing minefields, enemy artillery, and tank traps. Of the 15 tanks that started the attack, only one remained operational. One of the features of the battle was the Germans' use of Panzerturms—decapitated tank turrets mounted in fixed positions—and we visited one. The Italians had long ago removed the turret for the scrap value of the steel, but we saw the concrete pit that was below the turret. The regiment lost 593 casualties. Along with their neighboring unit, Seaforths, the Canadians in one day punched through the Hitler Line, which the Germans then abandoned.

At dinner, I had a delicious ravioli-like dish that was stuffed with cheese, and then an egg frittata dish that turned out to be completely inedible. Joining us in the dining room was a large group on the 2025 edition of the Stephen Ambrose tour I took in 2022. This time it was hosted by my favorite historian there, Chris Anderson.