Hal Jespersen's World War II Italian Campaign Tour, October 2025 [Part 2]

This is my (Hal's) report on a trip to examine the World War II Italian campaign sponsored by Valor Tours. This is my fourth tour with Valor and the second in which I am visiting Italy for WWII. The first trip to Italy was with Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours, but I was not fully satisfied with the amount of military content on that tour. So I am returning to Italy with a well-known expert on the campaign, Frank de Planta. I toured with Frank last year in France for the 80th anniversary of Operation Dragoon, and thought he did a fantastic job.

Since I took a lot of good photographs on the Ambrose trip in different weather conditions, I have included some of them in this report identified with "[2022]."

This is a lengthy report with a lot of photographs, so I have divided it into two parts:

Contents – Part 2

Saturday, October 18 — to Anzio

We started in Cassino at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery where there are 4,500 interred. It is split into two parts, with the British soldiers in front and the Commonwealth in the rear, and there is an Indian style to some of the monuments. We drove north on Route 156 and then passed through the Lepini mountains to the coast, where we drove north on the Anzio Plain.

We stopped outside the town of Latina to visit the Museo Piana delle Orme. This place is completely surreal. It's a former agricultural property that has giant sheds or barns, each jam-packed with collections of anything you can think of, as well as a complete military history of the Italian forces in World War II and lots of airplanes, trucks, naval vessels, and what have you. If I photographed everything of interest, there would have been literally hundreds of photos. So I attempted to be selective.

The first shed was labeled "Toys," but it was heavily focused on military models, including model soldiers, small battle dioramas, tanks, aircraft, and naval vessels. Hundreds, more than I have ever seen in one place. Next were three large sheds on the Reclamation of the Pontine Marshes, Vintage Agricultural Machinery, and [pre-war] Life in the Fields. An aero-naval park outside had lots of really obscure aircraft, including jet fighters from Fiat, and a half-dozen naval or Coast Guard patrol boats. Scattered between the sheds were a couple of railroad locomotives, a jet fighter, and a variety of farm animals that were penned away between the buildings.

The second half of the camp is focused on military history, like a Disneyland of World War II. There were exhibits about Italian concentration camps and rounding up the Jews after the German occupation. They described the transition from Italian prisoners of war to Italian Military Interned, IMI, and the brutal treatment they received from the Germans. Outside was a mock railway platform with a locomotive and train cars showing mannequins of Nazi officers and Jews being taken away. The shed about "Vintage Means of War" was mostly trucks and half-tracks, but they had a Sherman M4 and an M7 Sexton.

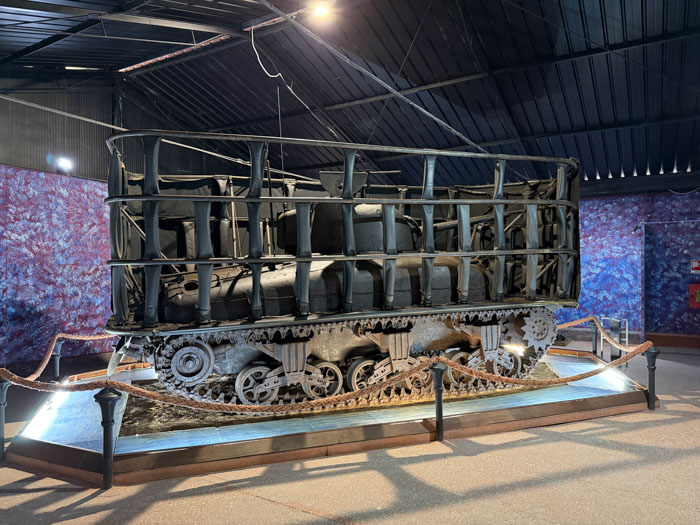

Then there were three sheds on the campaigns of the war involving Italians. The shed entitled "El Alamein to Messina" featured huge dioramas with life-size mannequins and military equipment, some with thunderous sound effects. (The exhibits also covered Italian activities in Africa well before El Alamein.) The campaign and battle descriptions were multilingual and very detailed with decent maps. One of my favorite parts was a Sherman DD tank that had been fished out of the sea, so it was a little rusty, but it had a full canvas flotation screen in place.

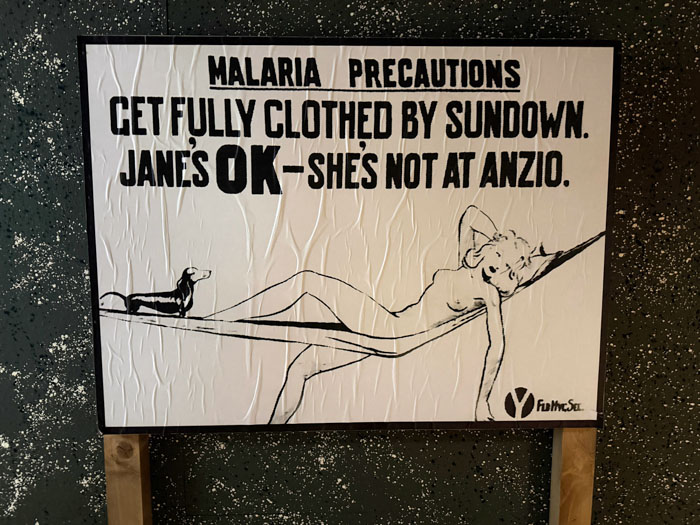

There was a shed each on Anzio and Cassino. Both had elaborate dioramas, and a lot of battle descriptions. The maps were good, although most were simply copied from original sources, translated into Italian. The battle descriptions were a little light, but offered no surprises. There was one panel that described the action of Italians on both sides of the battle, because some Italian units fought with the Germans. In the Anzio shed, there was a P-40L fighter that crashed off the beach and recovered in 1998. Also in Anzio was an exhibit about the spread of malaria. The Italians thought they had essentially eliminated it by the reclamation of the Pontine marshes, but a combination of German flooding of the area and supposedly some bacteriological warfare caused its return, which plagued a number of American soldiers.

The path to the exit led through a giant shop that was filled with thousands of army surplus items. These were not the modern Chinese knockoffs, but actual Italian Army surplus items. There were many semi-modern uniforms and a few artefacts that looked like they were of World War II vintage. I thought about buying a shirt, but apparently Italian soldiers are a little slimmer than I am.

We drove about an hour to Anzio and checked in to the modest Serpa Hotel, right across the street from the beach. There was no hotel restaurant for our nightly dinner, so we drove downtown with reservations at a beachfront seafood restaurant, Baia di Ponente. I had a seafood risotto and fried calamari. Pretty good.

Sunday, October 19 — Anzio

We started at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial in neighboring Nettuno. The grounds and facilities are immaculate. There is a video in the visitor center about the campaigns in Sicily and up to Rome (north of Rome is handled by the Florence cemetery), highlighting some of the men and women killed, now buried here. There are 7,861 graves and 3,095 names in the memorial hall for those missing. Many of the dead were relocated back to the States based on family preferences. Although everything was very moving, the highlight for me was at the far end of the property where a building held that memorial hall as well as a giant map room. The memorial hall has a large ceiling artwork that depicts the sky—stars, planets, and constellation symbols—exactly as they were at 2 a.m., January 22, 1944, the start of the Anzio landings.

Sitting in the beautiful weather on the cemetery grounds, Frank started a lengthy and informative session analyzing the key terrain of the Anzio battlefield and the planning for the invasion, Operation Shingle. Although the conventional wisdom is that Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, the VI Corps commander, was deficient in command and too timid to advance beyond the beachhead until he had built up a large force, Frank took the opposite view and was quite supportive of him. He described any effort to immediately advance to the Alban Hills with his small two-division force, as his orders from Mark Clark suggested, would have been snuffed out by the Germans within 48 hours. We also made a brief visit to a British cemetery for Anzio that had only about 1,100 graves. This one included soldiers only from the 1st British Division.

We drove on the Anzio–Albana road, which was the most important road on the battlefield, and saw how it gently rose at Aprilia (which is pronounced ah-PREE-uh), in the direction of the Alban Hills, an imposing landmark clearly visible from here. Mark Clark quickly became frustrated with Lucas building up his beachhead rather than advancing and pressured him to start a breakout offensive. On January 25, in the British sector, one battalion moved north and captured Aprilia. From there, on January 29-30, the 3rd British Brigade conducted a night attack in the direction of Campoleone with the Scots Guards on the right and the Grenadier Guards on the left. In an unfortunate incident, some officers of the Grenadier Guards advanced too far up the road and were captured by the Germans. The Irish Guards replaced the Grenadiers in the attack, but a one-day delay in getting this attack underway was directly responsible, in Frank's opinion, for accommodating the surprise arrival of the Hermann Göring Division in the American sector, which we will learn about tomorrow. The advance was costly, and among other losses, the Sherwood Foresters lost approximately 70% of their men, machine-gunned down in a railroad cut.

We made frequent stops along the way to highlight key landmarks and battle action, which I will not recount here. Frank pointed out the many ditches, called fossi, through which German troops would infiltrate inside and behind British units. By February 1st, the British had advanced their line into a narrow 2.5-mile salient, which Frank called a lozenge, extending to Campoleone railway station. Bletchley Park had intercepted and decrypted Enigma radio communications indicating that the Germans were planning to counterattack on February 3rd, so the British forces dug in as best they could. They were in a very difficult position because the salient would allow attacks from both sides that would cut them off.

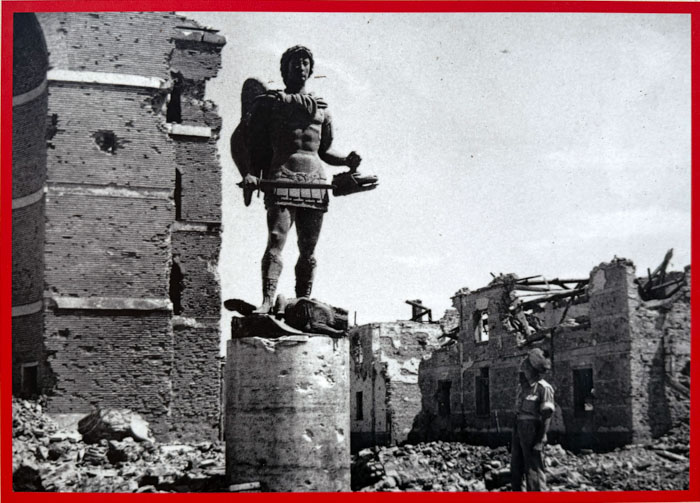

We took this opportunity for lunch and visited a large, modern shopping center that had a food court. All of us shied away from KFC and Burger King and went to Alice (ah-LEE-chay) for al taglio pizza slices. We did some exploring in Aprilia, which the Allies referred to as Aprilia Factory because of two towers that from the distance looked like they were industrial smokestacks. This was one of five fascist cities that were custom-built by Mussolini, and we found a couple of buildings that survived the destruction of war, as well as a metal statue of St. George the Dragon Slayer that was riddled with bullet holes.

The German counterattack was delayed and started on the night of February 7-8. We focused in particular on the attacks against the 5th Grenadier Guards. We walked around their overextended positions and saw how all four of their companies were put out of action by the German onslaught, leaving only the battalion headquarters with a handful of men. We went to an overlook position to see the headquarters in a quarry on Buonriposo Ridge and heard the story of Major William Sidney, who gallantly repelled attacks by two German companies, an action for which he received the Victoria Cross. By February 11, the British were falling back to an overpass called the flyover. They were in a very bad position indeed. We will finish up the British sector actions tomorrow. General Lucas was sacked by Clark on the 23rd and replaced by Lucian Truscott as VI Corps commander.

Our final stop after a long day of jumping in and out of the car all over the battlefield was a second British Cemetery, this one interring men of the 2nd Division. An interesting anomaly here is that the Royal Artillery erected an individual monument honoring about a dozen observation pilots who were killed in the area. The standards for these British cemeteries eschew any deviations from one identically designed grave marker per person. I got to see the grave of a driver in the Royal Corps of Signals, which was sentimental for me as a former U.S. Army Signal Corps officer. Their regimental crest features the god Mercury.

Before dinner, we drove to the port of Anzio to see the invasion monument there. Dinner was at the same seafood restaurant.

Monday, October 20 — Anzio

We returned to the Anzio–Albano Road to start on the second German counterattack of February 16–17. We stopped briefly at a monument on the Campo di Carne, which was unusual because it had simulated blood dripping from the top. On February 9, the British abandoned their exposed lozenge, leaving their heavy weapons behind. We drove to the final defensive line at a railroad overpass called the Flyover to examine the terrain and give a background to the battle. Because we received intelligence from Ultra, we knew that Hitler had meddled in the tactics of the battle and had demanded that the counterattack by seven German divisions be launched directly and serially down the main road.

Lucas, who was still nominally in charge of the VI Corps until the 23rd, planned an excellent defense. He arranged three regiments of the 45th Infantry Division in a bucket shape with the 179th Infantry in the center set to pull back under pressure from the Germans. Assuming that the two regiments on either side could hold, this would lure the Germans into a killing zone. He arranged a massive artillery bombardment and carpet bombing by the strategic air force. The defense worked exactly as planned, and the two sides fell into a stalemate phase from February 20th to May 23rd. During this time, the weather improved dramatically, and Truscott was able to bring in four more divisions for his eventual breakout. Frank reminded us that this stalemate period shows the futility of the Third Battle of Cassino because it was not needed to draw German forces out of the Anzio region.

We drove to an area that was riddled with wadis, an Indian term for ravine or creek bed, in which the U.S. soldiers sought refuge during the lengthy stand-off with the Germans. Before we saw one, however, we stopped at a monument to Eric Waters, who seems to have prominence solely because his son Roger was a member of Pink Floyd. He was also mentioned prominently on the port monument we saw last night. We also saw from a distance some caves in a cliff that the 157th Infantry defended on the left-hand side of the bucket. When we finally got down into a wadi, I found it quite miserable—very deep and a terrible place to spend a number of months in the rainy season.

Then we drove on a highway to the American sector, east of the Mussolini Canal. During the battle, this was an unfinished railroad embankment that the GIs called the Bowling Alley. Lucas ordered a breakout attempt by the Americans on January 29th, but if you remember from the discussion yesterday, the British attack was delayed while the Irish Guards and the Grenadier Guards switched their assignments. In that one day, the town of Cisterna was occupied by the Hermann Göring Panzer Division. The U.S. 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions were sent to occupy Cisterna, unaware that the Panzer Division was there, having performed a less-than-effective partial reconnaissance. The Rangers advanced with only light weapons in a wadi called Pantano Ditch and were invisible to the Germans until, halfway, there was an area where they had to cross a road and sneak past a German artillery battery. They eventually reached Ponte Rotta Road on January 30th and formed a defensive line. We didn't walk through the wadi, as the rangers did, but we followed them on a close parallel road up to this point. the German panzers on their flank opened fire directly down their line. Of the 777 men, only 7 were able to get out. We discussed all this at a place called Isola Bella, at which there are two stone columns that are riddled with numerous bullet holes. This is where the 4th Ranger Battalion, the ones carrying heavy weapons in the rear of the column, were hit by the Germans. We found a Ranger tab in one of the column holes that a recent Ranger visitor had left a few weeks ago.

We drove partway up Lepini Mountain to the village of Cori, where we could see the entire battlefield in a grand panorama. First, we stopped for lunch in a little place called La Taverna dei Golosi, where I had a pasta dish in the style cacio e pepe, one of my favorites. We consulted battlefield maps to examine the four options that Truscott considered for breaking out of the beachhead in May. Operations Crawdad and Grasshopper were rejected. Operation Turtle was meant to push northwest around the western slope of the Albin Hills. But this was rejected because there were two German divisions stationed there on good defensive ground, the 4th Paratroopers and the 3rd Panzer Grenadiers. However, Operation Buffalo offered advantages. It was an advance due north through the Valletri Gap to seize the town of Valmontone, which would cut off Route 6 to the German 10th Army that was withdrawing from Cassino. (The breakout from Anzio was intended to be done in conjunction with the Fourth Battle of Cassino, a combination called Operation Diadem.)

Clark reluctantly approved Truscott's plan for Buffalo, but warned him to be ready for ongoing operations. It kicked off on May 23rd and moved well, although 200 out of the 300 tanks in the force and 1,000 men were lost that day. By May 25th, the Americans had reached the outskirts of Valmontone when Clark ordered them to change their approach and take up Operation Turtle. Truscott was dumbfounded by this change, which made virtually no tactical or strategic sense other than to stroke Clark's ego by ensuring that the Americans would reach Rome before the British. Clark was able to capture Rome on June 5th but allowed the German Army to pass by unscathed. Frank quoted estimates that this decision cost the Allies as many as 200,000 lives by extending the Italian campaign.

We stopped near Velletri to discuss an action by Maj. Gen. Fred Walker of the 36th Infantry Division (whom we last saw down at the Rapido River). His plan to skirt around Mount Artemisio and come in around the back of Velletri broke through the Germans' Caesar Line and caused Kesselring to withdraw all of the German divisions to north of the Tiber. He accomplished all of this with Truscott’s approval despite the disapproval of Mark Clark, who wanted to concentrate everything on Turtle.

We drove for about an hour over and through the Alban Hills, where I got a glance at Castel Gandolfo, the Pope's summer residence overlooking Lake Albano. Then on the autostrada that circles Rome clockwise and ended up at a hotel northwest of the city, Relais Castrum Boccea. It is an unusual medieval-style set of buildings in a rural area. We had dinner in the hotel restaurant, which featured absurdly large portions. There were three courses, and I was able to eat only about half of each.

Tuesday, October 21 — Tuscany

The first rainy morning of the trip. We will follow the Fifth Army in its advance north of Rome. But our first stop was the MUSAM (Museo Storico dell’Aeronautica Militare di Vigna di Valle), the Italian Air Force Museum housed in a former float plane base on the shores of Lago di Bracciano. We spent about two hours visiting their collection. This is a beautiful museum with primo quality aircraft and all of the exhibits are translated into excellent English. Since I am not an Air Force history buff, I did not attempt to photograph all of the aircraft, some of which were quite unusual. But I have included some interesting ones and some panoramas.

I was attracted to an outlandish World War I bomber that looked like a Rube Goldberg contraption and must have taken real cojones to fly. There was a collection of sleek racing aircraft custom-built for international competitions in the 1920s, looking like they were designed by Ferrari or Lamborghini. And an extremely early jet plane that was built in 1940 but was never produced. It had an unusual jet engine that featured a compressor operated by a piston engine.

The museum exhibits are very frank about the limitations of the Italian aviation system and the Italian Air Force in World War II and up until today. They portray the military program of the 1930s as more of a jobs program than a serious effort, and they had an inability to concentrate on a few effective designs. They have a lot of information about the pioneers of Italian aviation, none of whom anyone has ever heard of. At the entrance to the museum, there is a small model of an F-35, but inside, the most recent airplanes are an F-16, a Tornado, and a Typhoon. One of the unintended highlights for me was outside on the grass where a family of nutrias were munching down frantically.

Immediately following the capture of Rome, the Fifth Army was on the move again in pursuit of the Germans who were withdrawing to the Dora line, which was intended as a non-defensible rallying point before they withdrew as an organized force to the Albert Line over the Ombrone River at Grosetto. We studied maps showing the course of the VI Corps following the coast to Civitavecchia and the II Corps moving due north to Viterbo. However, the pursuit was delayed by a Clark reorganization. The French Expeditionary Corps replaced the II Corps, and the VI Corps headquarters was withdrawn, replaced by a brand-new IV Corps HQ. The latter move was taken so that Truscott could begin planning Operation Dragoon, scheduled for less than two months from now. Dragoon would prove to impose an enormous hit on the Fifth Army because it shrank from 390,000 to 171,000 men, including the loss of many logistical, armor, and artillery units.

We drove northwest on Route 1 into Tuscany to follow the advance of the 36th Infantry Division. Fred Walker was still in command, although Clark had notified him that he was sending him back to the States to command the Infantry School. A new, untested Maj. Gen. John Dahlquist would replace him. We passed through Tarquinia, and once we reached Orbetello, the three regiments of the division took separate paths to the Albert Line. While the 143rd Infantry Regiment moved up the coast, the 142nd moved through Magliano, and the 141st northeast to Triana. We followed the 142nd and stopped in Magliano, which is a beautiful medieval town on a hill. It had 40-foot walls, and Company F of the 142nd took over 10 hours to secure it on June 14th. We had a great view of the beautiful terrain to the north, and Frank described the advance of the 142nd, including the exploits of Staff Sergeant Homer Wise. He performed amazingly valorous feats in attacking German units by himself and received the Medal of Honor.

On the 16th, the 142nd and 143rd crossed the River Ombrone and reached Grosseto. The German forces had abandoned the Albert Line, so this was an easy operation. We continued our discussion of the advance north. The new corps commander, Willis Crittenberger, had come in with no previous combat experience, but he surprised his staff with a bold plan for advancing. He needed to get the 34th Infantry Division and the 1st Armored Division to reach east-west Route 68. The staff's inclination was to send the tanks on an easy road near the coast and the infantry through the mountains further east. However, Crittenberger realized that all of the German anti-tank forces would be near the coast. So he switched it up, and the 34th Infantry Division moved along the coast while the tanks moved in three columns through the difficult mountain roads, an impressively successful movement. We followed the easier route on modern state roads.

We drove quite a way north to the town of Casino di Terra, southeast of Livorno, and checked into the Hotel Fattoria Belvedere. It is an attractive property, but once again the rooms are quite modest, and I was perplexed to find a hotel in 2025 that does not have Wi-Fi in the rooms. Dinner in the hotel was pretty good.

Wednesday, October 22 — Tuscany

Our second rainy morning, but it diminished by 10:30. We decided to fiddle with the itinerary and forsake a long ride to the outskirts of Florence because most of the drive could be substituted by a map-reading session. (Frank’s map pack is excellent.) The only landmark we missed was the big American cemetery outside Florence.

We drove back to near the coast and the town of Rosignano Marittimo to discuss the advance of the 34th Division to Livorno and the Arno. We climbed up a rather steep hill to see beautiful views of the surrounding countryside and orient ourselves to the terrain. There were two ridges: One on the coast traversed by Route 1, another traversed by Route 13, and a valley in the middle traversed by Route 206. The Germans of the 26th Panzer Division defending Livorno expected the valley route to be the primary axis of advance, so we needed to avoid that. Crittenberger once again implemented a clever approach. The coastal route was traversed by the 804th Tank Destroyer Battalion and the 135th Infantry Regiment. The inland ridge was traversed by the 440th Infantry Regiment, the 168th Infantry, and the 363rd Infantry. Our position in Rosignano was taken by the 135th after two days of fighting.

While up on the hill, we also discussed Alexander's plan for breaching the Gothic Line, north of Florence, which we will not see on this trip. The British Eighth Army resisted his idea of attacking directly north from Florence and wanted to move to the east coast of the Italian peninsula. Alexander ordered Mark Clark to cover the Eighth Army's original starting line, but he refused until Alexander agreed to transfer the 13th British Corps to his command. Frank offers a 9-day tour that starts in Florence and covers the events around the Gothic Line until the end of the war and I hope to be able to take that sometime next year.

We drove on Route 68 to Volterra; that east-west road was the objective of the 1st Armored Division that we discussed yesterday. The 1st AD stopped here, exhausted from its tough transit of the mountains, and was replaced by the 88th. There were stunning views of the countryside, but weather conditions made them difficult to photograph. We continued on a very long drive past the historic towns of Siena and Orvieto and stopped for lunch outside the latter. We passed by the northeast of Rome and entered the Alban Hills. Here we stopped at a small café high above Nemi Lake, where we enjoyed a magnificent view of the lake and Anzio, 45 kilometers in the distance. This reinforced in our minds the strategic importance of these hills.

Our hotel for the final night is Villa Artemis Monte Artemisio Resort and we had dinner in the hotel restaurant, an excellent carbonara and bistecca con patate fritte (steak frites equivalent).

Thursday, October 23 — Flying Home

Frank drove us to FCO. I had about six hours before my flight, and United wasn’t open to accept my bag for the first hour. FCO departures are a real zoo. It took about half an hour to get through customs and security. I was eligible to go to the Prime Vista lounge, which was extremely crowded but comfortable. The United flight was comfortable, and I got home about 8 p.m., Pacific time.

I had a really excellent time on this trip. The military content was exactly what I was looking for, and I now know a lot more about the strategies, tactics, and terrain, and about Cassino and Anzio in particular. Frank was an outstanding guide as he was on the previous trip, and I am hopeful I will be able to schedule another trip with him next year to continue the story of the Italian Campaign.