Hal Jespersen’s World War II Tour of Poland and Berlin, September 2025

This is my (Hal's) report of my trip to discover World War II Poland (and Berlin) with Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours. It is my sixth outing with this group and the fourth with Chris Anderson, lead historian.

Since this is a long report with 350+ iPhone 16 Pro photos, I have broken it into three parts:

- Gdańsk, Wolf’s Lair, Warsaw (this page)

- Kraków, Auschwitz, Wrocław, Stalag Luft III

- Kostrzyn, Seelow, Berlin, Potsdam

Tuesday–Wednesday, September 2–3 — to Gdańsk

I flew SAS overnight from San Francisco to Copenhagen and then the brief transfer to Gdańsk, the former German city of Danzig. SAS has no lounge at SFO—too bad they dropped out of Star Alliance—but I was granted access to the Air France Sky Team business class lounge, which was very nice. The flight was good, but my seat was rather lumpy and uncomfortable in the lie-flat configuration, and the USB ports were inadequate to recharge my iPad on the 10.25-hour flight. Luckily, I always cart around a few power banks. (I found out on my return flight that this front row seat is much easier to get into than the seats farther back.)

Copenhagen’s Kastrup airport is one of the quietest large airports I have ever encountered. It is quite clean, although the SAS lounge is not up to boozy business class standards as in San Francisco, but still fine. Border control took less than two minutes, including navigating the line and then pleasant chatting with the officer about my Danish surname. The flight to Gdańsk was 40 minutes on a small regional jet. It was great to see my bag get loaded on the plane just as I boarded. I picked up my bag less than 10 minutes after touchdown. I have recently been using a car service called Welcome Pickups, and once again, I was very happy that I did. The driver was right on time, and we had a great conversation about all of the places that I ought to visit. Which essentially matched an itinerary that ChatGPT had given me. One amusing interchange was when he recommended a sheep museum, which I thought was cool because I actually like sheep a lot, and I asked him whether they had live sheep at the museum, and he was very confused. It turns out that he was actually talking about a ship museum.

I was dropped off at the Radisson Blu Hotel, right in the center of the busiest tourist area, which my driver called the "New Old Town." (I found out on Friday that this area is more correctly called Main City.) During the war, this area was 90% demolished by the Soviet invasion in March 1945, but the Poles have been rebuilding it from scratch using styles of buildings from pre-war times, in many cases Renaissance architecture. This will be the group hotel for two nights, but I am arriving a night early to accommodate flight schedules. It is a moderate European hotel with relatively small rooms, but comfortable enough. I got a free drink coupon for agreeing to no maid service during my stay.

I am staying in a top-floor "executive room," which has an unusual feature that provides a minibar with unlimited free access for the first night of the stay only. The lady at the front desk said that some people fill their suitcases with stuff. But I found that the pickings were rather slimmer than what you would find in a typical American minibar. I took a brief walk around the Long Market area looking for an ATM that did not have exorbitant fees, which most here do. I passed by dozens of attractive restaurants with outdoor seating in the beautiful late summer weather, but it was past my dinner time, so I just subsisted on the memories of snacks that I got on planes and at airport lounges.

Thursday, September 4 — Gdańsk on My Own

I enjoyed a typical European hotel breakfast buffet and could not differentiate it from a German version. Today is a really beautiful day, sunny in the upper 70s. Main City’s Long Market is completely swarmed with guided tours, many of them in German, which seems ironic given the history of the city. I walked down the main street and stopped at Neptune's Fountain and then saw the outside of Artus Court, a gathering point for the 16/17th century mercantile elites. It was named after King Arthur for some reason.

St. Mary’s Basilica was built mostly in the 15th century from one million bricks, the largest such church in the world, capable of hosting 25,000 worshipers. The interior is quite beautiful, but the highlight for me was an extraordinarily complex astronomical clock from 1464. There are 405 steps up to an observation deck with panoramic views of the city, but I demurred. An impressive organ with 3200 pipes was relocated from St. John’s church to replace the original that was destroyed in the war.

I walked down picturesque Mariacka Street, which is home to many jewelers, street vendors, and amber stores. I took a brief walk along the Motława River, a tributary of the Vistula, to which I expect to return later in the day. But I wanted to see a monument to Daniel Fahrenheit, who was born nearby in 1686. The monument contains a mercury thermometer similar to the one he created in 1752, although it was not his first simple invention (1714).

The Main City Hall is now a museum, which offers the opportunity to climb stairs 80 m up and get another panoramic view, but once again I did not indulge. The museum has exhibits about Pomeranians who were drafted into the German army, the impressively decorated Great Council Hall (Red Hall), the destruction and rebuilding of the city, a lot of very impressive armoires and other furniture, beautiful silver pieces, and the importance of animals during and after the war.

Back at the riverfront, I had lunch at a modern restaurant specializing in pierogies—Stary Młyn Piergarnia. (That second word, meaning mill, is pronounced mwin.) I had a special that offered three different oven-baked dumplings (Piecuchy style, versus the boiled version, Lepiochy) with a large salad and a beer for $22. An excellent meal and quite a good value. Then I hiked down the river to the National Maritime Museum. (This is the one that I thought was a sheep museum.) I was rather disappointed in it. It had three exhibits: a room full of cannons from a Swedish ship that had been sunk in 1627; photographic memories of foreign naval courtesy calls in the nearby port of Gdynia from the 1920s through the 1990s; and an exhibit about ancient boat building techniques and trade practices, which was marred by its lack of English language translations of the signs. There was also an old cargo ship, the Soldek, that you could pay extra to board, but I have hit my head too many times on low-hanging pipes and small hatches on old ships to bother with that again.

I set off on a hike to the Amber Museum, recommended by my driver. But after a half mile or so in the very warm afternoon with my feet sore from severely cobblestoned streets and still retaining a little bit of jet lag fatigue, I decided to bail out and return to the hotel in mid-afternoon. Our Ambrose group convened at 6:30 for a brief introduction of the two weeks to come. Our historian, Chris Anderson, gave a short history of Poland from 1919 until 1939 and described our planned activities for the first few days. We met our tour director, Marta Skirlo, and our bus driver, Sylvester. There are 33 guests on the tour. Then we adjourned to the hotel restaurant for a buffet dinner. It is unclear to me whether any of the entrees we had were particularly Polish in orientation.

Friday, September 5 — Gdańsk

We started early for a walking tour of the main city with a local guide. She pronounced the city name with only a barely audible G, like “Dyngsk”. (On the other hand our Polish driver Sylvester pronounced it with a more audible G, so I guess dialects vary.) She pointed out the Renaissance architecture used to rebuild the district, a deliberate choice to minimize any Germanic flavor, and to tilt more in the direction of Amsterdam architecture to relate to the many Dutch shipbuilders that worked in the Polish shipyards. The tour was focused on city history, a highlight of which was the speech by Hitler on September 19, 1939, at the Artus Center. He had wanted to do it in Warsaw, but the stubborn Poles held out too long. Chris read a passage written by William Shirer, who had attended the speech. We looked at the outside of Main City Hall and then walked through St. Mary’s Basilica to discuss the war damage. On Mariacka Street, she pointed out a bas-relief of the goddess Diana, which during renovation in 1957 had a tiny lunar lander slyly carved into the moon over her head. (This was inspired by Sputnik, not the US Apollo program.)

We walked to our bus and drove about 20 minutes north to Westerplatte, a peninsula and port on the Baltic Sea where the first shots of World War II in Europe were fired. The German battleship Schleswig Holstein had arrived a few days earlier on a courtesy call but opened fire on the small group of defenders of the port. It was anchored in a spot referred to as Five Whistle Bend, a narrow passage where ships would have to whistle to avoid hitting each other.

We started at a guard house that had visible markings of machine gun and shell fire, which had been relocated 80 m away after the adjacent narrow channel was widened. Guard house number 5 is memorialized with its only foundation remaining. Our guide told us the story of the troops under Major Henryk Sucharski, who had been ordered to hold out for 12 hours, but yet they did so for seven days before having to surrender without any food or ammunition remaining. We visited the outside of New Barracks, now just a broken shell of concrete, which mostly survived the German bombardment but not the demolition activities during the war and in the Soviet era. Finally, we visited a modest hill upon which is mounted a tall concrete monument to all of the Polish defenders of the coast.

We drove toward downtown to the now mostly deserted shipyards. The old post office here is a place where historic resistance occurred on the first day of the war. I was expecting it to be right in the middle of a dense downtown area, but in fact it is in the city’s outskirts. The Germans were quite incensed that the League of Nations had retained control over the Danzig post office and telephone systems, so they targeted this particular post office. The men inside, who had had some military and resistance training, were expected to be overwhelmed immediately, but in fact lasted 12 hours. It was only after the Nazis dumped petrol into the basement and set it on fire that the defenders had to surrender. The Nazis were quite cruel to the prisoners and tortured them and eventually executed them, burying them in a mass grave that was only discovered in the 1970s. There is now a small museum inside, but we did not enter. Instead, we walked a couple of blocks to the relatively new Museum of the Second World War.

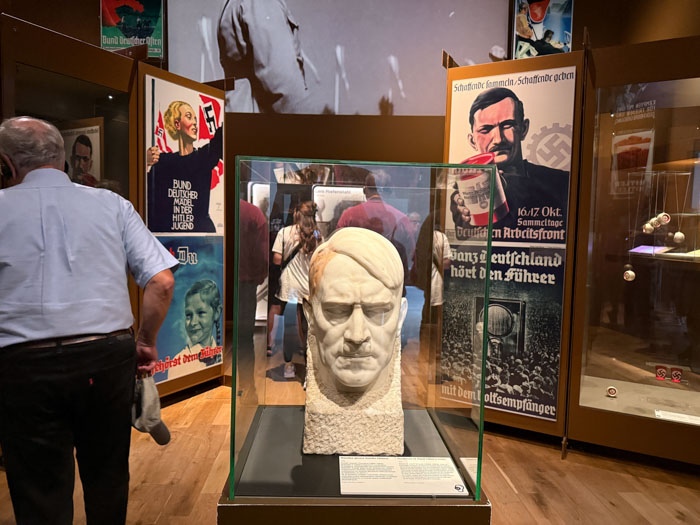

The WWII museum is the largest such in Europe with 5,000 square meters of exhibition space, although the building itself is quite a bit larger than that, so it is unclear what is going on with the rest of the space. It is very stylish and has excellent audio-visual design, including headsets that are geo-located so that the narration is focused on your exact location. That's a good thing because the exhibition space in the third sub-basement is deliberately quite dark for thematic reasons, and there are warrens of little rooms that are as confusing to navigate as an IKEA store. It does not present a narrative similar to the average World War II museum, such as the one in New Orleans, that covers the variety of campaigns in the war, and has room after room of maps, tanks, artillery, weapons, and uniforms on display. Instead, it emphasizes the terrible parts of the war, including the Holocaust, ethnic cleansing, mass migration/displacement, starvation, horrific mistreatment of POWs, and bombing of cities. They also justifiably played up the Polish contribution to the fighting and resistance. Fortunately, they had two tanks on display: a Sherman Firefly in immaculate condition, and a Soviet T-34. The museum was entirely European-focused.

The museum closed early today for a special anniversary celebration, so we returned to the hotel and had part of the afternoon free. A thunderstorm moved in, just as the weathermen predicted, and cooled things down a bit. Dinner was a buffet in the hotel again, which I don’t enjoy, so I went off on my own and wandered around Main City in search of my traditional Friday night pizza. (Little did I know at the time that all of the hosted dinners coming up would be mediocre buffets, except for the farewell dinner on the final night).

Saturday, September 6 — Wolf’s Lair

We drove to Solidarity Square in the old shipyard for a brief lecture by Chris. We didn’t go into the museum. Chris covered the history of shipbuilding here, Teutonic knights, and the Hanseatic League. The shipyards were heavily used by the Nazis, particularly for U-boats; when the city fell in March 1945, there were 45 still under construction. The city was a major evacuation point for German troops and civilians trying to escape the Soviet army, but the process was a frantic mess, particularly when a battleship was sunk, blocking the harbor.

Chris described the unrest and strikes in the 70s and 80s, centered on the shipyard. The army killed 40 or so strikers in the 70s, and the giant monument here is dedicated to the fallen. Marta and Chris referred to the controversial legacy of Lech Wałęsa, who in a divided polity today is either loved or hated. Apparently, he is considered a crackpot by some, but we didn’t discuss any specifics.

We started on our 4-hour bus ride and passed a monument at the train station to the Kinder Transport. It commemorates the transports of Jewish children to England, organised by the Jewish community before World War II from Nazi-occupied areas. Chris narrated a brief history of the Polish people long before the 20th century, and then through the world wars and into Soviet domination. Then we watched a DVD of the Tom Cruise movie Valkyrie to give us a flavor of the Wolf’s Lair. We had a rest stop at a big shopping center. I stopped at a small gofry (waffle) stand for a snack. Lunch was a bagged sandwich provided by the hotel. Edible.

The Wolf's Lair (Wolfsschanze) was Hitler's headquarters near Kętrzyn (née Rastenburg) in East Prussia from 1941 through 1944. It took 2,000 men to build this large complex of bunkers, and Hitler stayed there for more than 840 days on and off from the start of Operation Barbarossa to the abandonment in the face of the advancing Russian army in November 1944. I was surprised to see at the entrance that the place was being visited by hundreds of cars and a number of buses. There is a big restaurant, a hotel, and a gift shop, so it is quite a tourist mecca even though it is way out in the sticks. We took a two-hour walking tour with a local guide who was quite animated and knowledgeable, and I was able to understand at least 90% of her talk despite her accent.

We stopped by about 20 massive bunker buildings, some of which had 2-meter concrete roofs, and more recent ones that had 6-meter. As many were similar, I did not photograph each and every one. All were in various states of collapse, not caused by damage during the war, but by deliberate attempts at demolition by the Soviets afterward. One building was tackled with 12 tons of TNT, and the roof is collapsed, but most of the concrete is still there unharmed. Another was the building in which the Operation Valkyrie assassination attempt occurred, but there is virtually nothing left of it. There were bunkers specifically allocated to Hitler, Martin Bormann, Alfred Jodl, Wilhelm Keitel, and Hermann Göring, the latter of which was enormous and had anti-aircraft cannons and heavy machine guns on the roof.

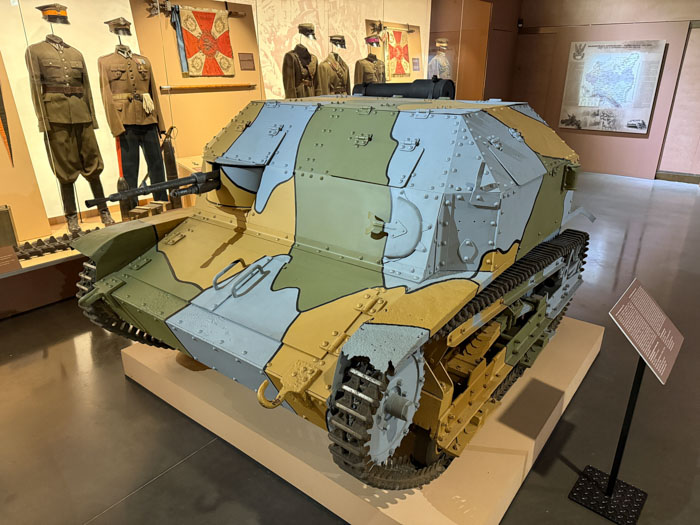

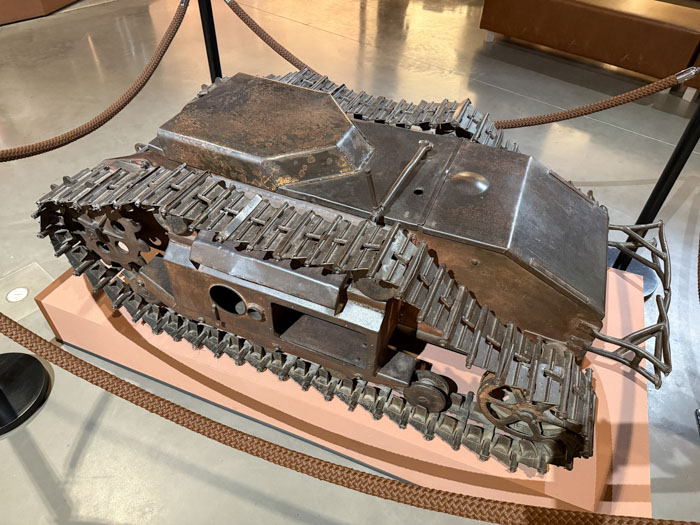

One building was a small museum separated into two parts: A general overview of the causes of the war and the consequences, which we breezed through because we have certainly seen that sort of display before; and a detailed account of the Operation Valkyrie assassination attempt. There was a recreation of the room in which the bomb was planted with mannequins of Colonel von Stauffenberg and Hitler. One new thing I learned was that a few hours after the bomb went off, Hitler hosted Mussolini and gave him a tour of the bombed room. Another building had artifacts that had just recently been unearthed, as well as a Jagdpanzer 38(t) "Hetzer," which was painted to have some connection to the Poles that I did not understand. This tank destroyer was actually built on a Czech armored platform.

There was a 45-minute bus ride to the small city of Ryn, where we checked into an unusual hotel called Zamek, which is housed inside a 14th-century castle built by the Teutonic Knights. The hotel is rustic and filled with medieval decorations, suits of armor, etc. Dark hallways wind around, up and down stairs, in unpredictable ways, and it is easy to get lost. Harry Potter might feel at home here. There is a large ballroom decorated in medieval themes, and there was a big party going on for most of Saturday evening. I have a miniature single room. Dinner in the hotel restaurant was another mediocre buffet.

Sunday, September 7 — Grunwald and Warsaw

There were noisy thunderstorms in the early morning, something that I, as a Northern Californian, don't get to experience very often. The Polish Weather Bureau was able to send English-language text message alerts to my phone, even though I never registered with them for any such thing, warning about these thunderstorms and potential flooding in the area.

We bussed almost two hours east. Along the way we started watching a British video series by Ian Kershaw called The Nazis, A Warning from History. We reached the battlefield of Grunwald, a decisive battle between the forces of Poland–Lithuania and the German Teutonic Order on July 15, 1410. This is sometimes referred to by the Germans as the First Battle of Tannenberg. (The Second Battle was fought about a hundred miles away from here during the First World War.) Our first stop was the visitor center that included a large bookstore with all of the books in Polish. Fortunately, the accompanying museum (quite stylish) had multilingual exhibits.

We marched up a long hill and passed two very large monuments to the battle, and then stopped at a giant stone map. The Stone Age cartographers who created this present the battle in a very schematic, static way and did not orient it to the terrain or the direction of the forces. Chris gave us a detailed description of the battle, which resulted in the rout of the German forces. More important than the battle details were the romantic and mythical impact that extended into the 20th century. The Slavs remember that they were able to repel the invasion by Western Europe, and the Germans treated many of their victories in the two world wars as retribution for their defeat here. The Teutons had an attitude that they were stabbed in the back, very similar to the German reaction after World War I. Their garb, white with a black cross, was symbolically adopted throughout the world wars, particularly some tank insignia.

The museum is very nice and presents all of the origins of the forces and the results of the battle, not so much the battle detail. There is a multimedia presentation that shows lots and lots of close up sword fighting. It was interesting to see the early primitive precursors to artillery used during the battle, which had more of a psychological impact than any kinetic combat value. There was also a model of Malbork Castle, the headquarters for the Teutons, that was besieged after Grunwald.

On the 2.5-hour bus ride to Warsaw, we consumed our bag lunches from the hotel. I supplemented mine with a spicy chicken pita I bought in a shop next to the museum. (The shop called it a pita, but I think it was actually a Turkish dürüm, a cone-shaped wrap with doner ingredients inside, crisped up in a panini press.) We stopped at the Polish Army Museum, which opened recently (replacing a longtime communist version). This is going to turn out to be a really cool museum, but it is not fully open. There is one room that covers 20th-century history, but there are others going back to the 13th century that are empty or closed off. There is a brand-new Polish history museum next door in an immense, very stylish building. Only a portion is open. I was very impressed with a couple of things about the Army Museum, the most important being their superb cartography. Those guys did really complex maps with hundreds of events, and they are very clearly documented, although all of the labels are in Polish, so it is difficult for an American to follow some aspects. (The very complex legends are, in fact, multilingual.) Also, they have about a dozen armored vehicles in really outstanding condition, the majority out behind the building. Almost all of them are Soviet models, but it is surprising that the most modern one in the bunch is only a T-55.

Our hotel in Warsaw is the Bristol, an Art Deco luxury property near the presidential palace, built in 1901, now owned by Marriott. It was one of the few buildings left standing in Warsaw at the end of the war, and that is because the Germans used it as their local headquarters, so they did not harm it, and for some reason, the Soviets didn’t either. In any event, it is a significant step up from the two previous hotels on the tour. Dinner in the hotel was once again a buffet, but this one was improved by having some Polish specialties and a higher quality level than the previous hotels. The only downside is that drinks at the bar are significantly expensive.

Monday, September 8 — Warsaw

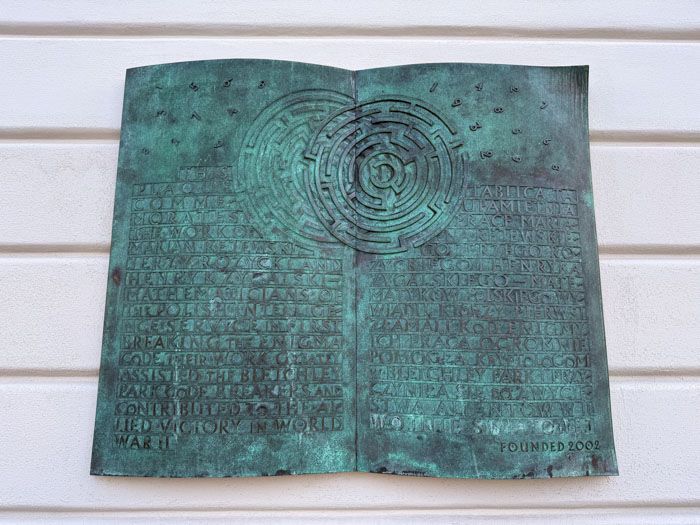

After an excellent buffet breakfast, we started on a brief walking tour with local guide Eva. We found a memorial plaque to the Polish mathematicians who did the original research here to break the German Enigma code. In Pilsudski Square, which had been temporarily named Adolph Hitler Platz, we came to a small surviving portion of the Saxon Palace: three arches that are now the resting place of the Unknown Soldier. Moving into the beautiful Saxon Garden, we found one of fifteen Chopin benches—a seat with a plaque and a button that plays a famous Frédéric Chopin tune.

We boarded our bus and drove to the southern border of the Warsaw ghetto. Dismounting, we witnessed the differences in architecture here. Standing next to a dramatic skyscraper, one of many in Warsaw, we had a good view of the 1950s-era Palace of Culture and Science tower given to Warsaw as a “gift” from Joseph Stalin. About 80 percent of the buildings in Warsaw were destroyed during the war.

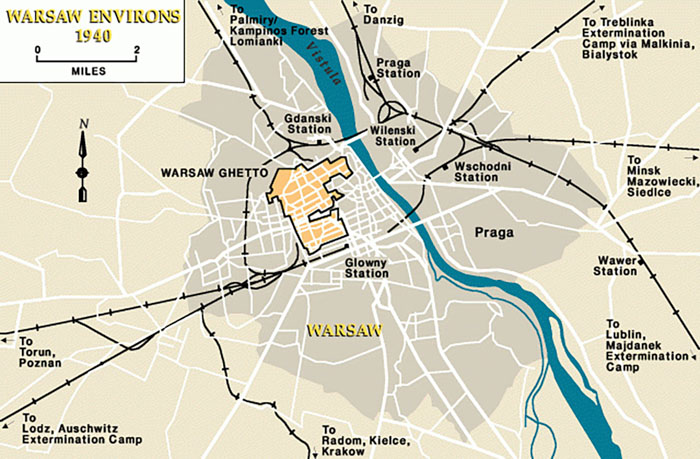

Eva has an encyclopedic knowledge of Warsaw and Jewish history in the area, and she proceeded to educate us. During the initial invasion of Poland, Warsaw resisted attack for 28 days and suffered from significant Luftwaffe bombing. The roundup of Jews did not occur for at least a year while the Germans contemplated how to handle them. They created an organization called the Judenrat in November 1940 that was responsible for administering the Jewish population and which laid out the borders of the Warsaw ghetto. These borders changed over time, and Ava emphasized that if you want to look at a map of the ghetto, you need to ask “when?” The ghetto was surrounded by 12-foot walls, about 12 miles long. Jews were given ration cards for food that allowed them 250 calories per day, a starvation diet, and as many as 100,000 Jews died in the first year, including those with diseases such as typhus.

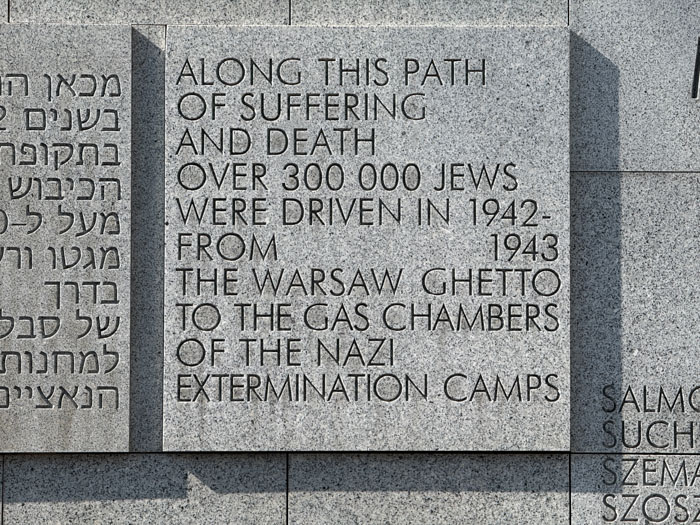

The Nazis' Grossaktion—mass deportation and extermination—began in July 1942. Over 300,000 Jews were herded onto trains and shipped to the Treblinka extermination camp, where they were immediately murdered. Almost none of the Warsaw Jews were sent to the more famous camp, Auschwitz. In a three-year period, Auschwitz murdered about a million Jews and others, but Treblinka almost equaled that number in 13 months. We paid a brief visit to a shop owned by a young couple that has a mission of finding mezuzah traces. A mezuzah is a small rectangular box that contains a parchment with a passage from Deuteronomy attached to the side of a door frame. When these are removed, it leaves an indentation or slot or trace. This couple has made it their mission to find and document as many of these traces as possible.

We drove north to a spot where there was a long sliver of access through the middle of the ghetto to accommodate an important courthouse. Because the Nazis did not allow the Jews to leave the ghetto, they erected a tall footbridge that went over this gap. In 1942, the footbridge was removed. And eventually, the southern or smaller part of the ghetto was collapsed, and the larger portion had to accept all of the relocated Jews from the southern portion. Eva also described other boundary changes, such as removing a cemetery from the outskirts of the ghetto that was used quite brazenly by food smugglers.

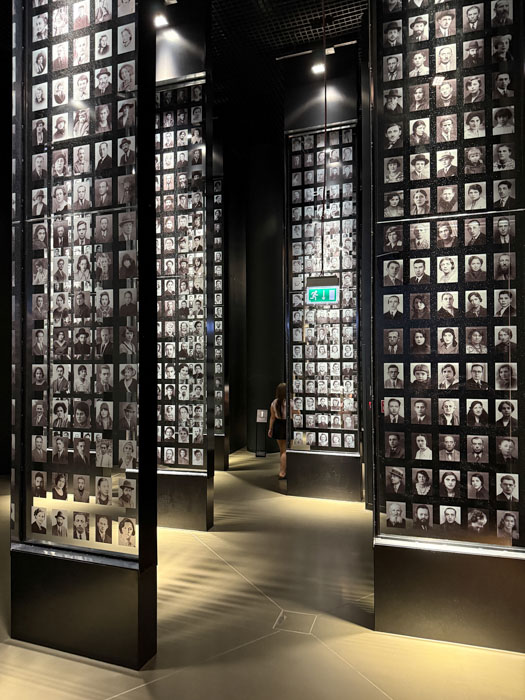

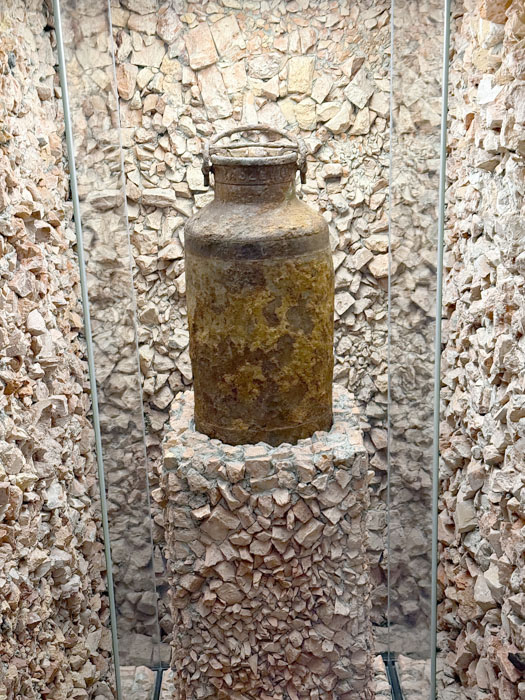

We visited the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute to learn about the effort of a small group of ghetto residents to secretly amass documentation about their lives so that they would not be lost to history. The Institute is housed in a building that was next to the Great Synagogue, which was blown up by the Nazis. There is some evidence of damage to this building as well. There are a number of letters from Jews who well knew that they were on the way to their deaths as last testaments. They were quite heartbreaking as they said farewell to their friends and family, only wishing to ensure that they were remembered.

We had an unhosted lunch at a shopping center/galleria in a restaurant that served Polish dishes, cafeteria-style. I had stuffed cabbage, and a number of other people had pierogies. Then we traveled to Umschlag Platz, the place Jews were taken to be loaded onto the rail cars. There is a memorial that is shaped roughly like a cattle car, and inside is a wall with 450 engraved first names, each representing one thousand Jews that were exterminated.

We visited the Miła 18 memorial, which marks the site of the main bunker for the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) during the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, where Mordechai Anielewicz, its 24-year-old commander, and many fighters perished. Most fought until their last bullet and then committed suicide, which some consider to be the equivalent of a Warsaw Masada. The memorial consists of a mound of rubble, believed to cover the entombed fighters, with steps leading to a circular paved area featuring a tri-lingual obelisk with inscriptions and names. I was confused at the time about terminology. This ghetto uprising in 1943 is distinct from the much larger Warsaw Uprising of September 1944.

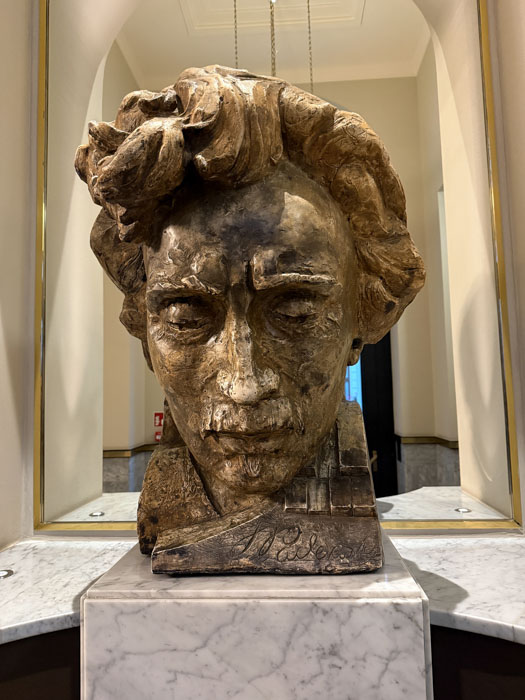

Next was the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes, a large marble slab that had memorials on each of two sides. On the eastern side was the March of Death— persecution of Jews at the hands of the Nazis. The western part of the monument shows a bronze group sculpture of insurgents—men, women, and children, armed with guns and Molotov cocktails. The central standing figure of this frieze is that of Mordechai Anielewicz.

Our final stop of the day was the [1944] Warsaw Uprising Museum. I was disappointed with this visit. The museum has many exhibits, but the entire space is very dark, making the bilingual exhibits difficult to read and the whole place difficult to navigate. The curators must assume that most of the visitors will be locals because they make liberal use of unfamiliar street and district names. There were some interesting aspects. There is a replica of a B-24 Liberator hanging (in the dark) from the ceiling representing the food and weapons supply efforts by flights from Brindisi, Italy; many, if not all, of these U.S. 15th Air Force flights were piloted by Polish crews. There is also a 3D film that flies you over the city showing the absolute devastation as of the spring in 1945. Another film shows scenes of the uprising. Somewhat inexplicably, there is also a hall that is dedicated to GROM, a modern Polish Army special forces operation that has been modeled on the U.S. Army Delta Force.

We had dinner on our own tonight, and I walked about a quarter mile to a nice Polish sidewalk restaurant called Gościniec Polskie Pierogi. I had a dish called Staropolski Bigos, which is a typical dish of hunter's pork stew with sauerkraut, sausage, forest mushrooms, and sliced dried plums, served in a bread bowl. Dessert was a collection of four sweet pierogies, including my favorite stuffed with a sweet cheese filling.

Tuesday, September 9 — Warsaw

Another buffet breakfast, another two-hour walking tour, this time focusing on Old Town Warsaw. The Presidential Palace is directly next to the hotel, and I can look down upon it from my room window. Eva described various Polish governments over the last 300 years. The palace was the site of the first public concert by Chopin, aged 17, and also the Solidarity Round Table Conference of 1989. Down the street was a plaque about Maria Curie–Skłodowska, aka Madame Curie, who was born in Warsaw and had a lab in this particular building. We entered Old Town with its medieval architecture. It had been reduced entirely to rubble during the war, including the 14th-century royal castle. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site, which was a controversial decision because the construction is entirely new, but many of the original damaged materials were reused, and they took care to use appropriate building practices of the time.

Next was the Archcathedral Basilica of St. John the Baptist, originally a 14th-century church. In the 19th century, it was changed from Masovian Gothic architecture to English Gothic Revival. After its destruction in the war, it was reconstructed to its 14th-century appearance. In the church is a monument to Ignacy Jan Paderewski, who was not only a noted classical pianist but the Prime Minister of Poland, who signed the Versailles Treaty in 1919. We walked through Market Square, which originally had a town hall in its center, but now features a fountain installed in 1855 with a statue of a mermaid brandishing a shield and sword. Eva said no one could explain why a mermaid is the symbol of a landlocked town. But she said there are multiple mermaid statues within the city limits.

We examined reconstructions of the old city defensive walls, including a relatively rare barbican structure that is built on a semi-circular design that prevented a single enemy cannonball from bursting through two successive gates. Nearby is Madame Curie's birthplace, but the house was not photogenic. At the City Archive building, Eva described how it was used as the main hospital during the uprising. As the uprising failed, the Nazis went through executing all of the patients. She also talked about 1943, where the Germans created terror in public by gathering up people on the street at random and gunning them down. At the Field Cathedral of the Polish Army, we stood inside a narrow space with the surrounding walls covered in the names of 22,000 soldiers murdered by the Soviets.

Eva pointed out a manhole cover and described how 11,000 people (soldiers and civilians) escaped from the besieged Old City as the 1944 uprising began to fail. They had to traverse from 1 to 3 miles in a very narrow sewer without lights and without making a sound. The passage could take up to 20 hours. At the Warsaw Uprising Monument, we admired the architecture and took a group photo. At this point, Sylvester and the bus picked us up to head to our next stop. Along the way, Eva described how the Polish Home Army was treated as criminals by the Soviets and she described Operation Tempest, the organized resistance of 1944 with the famous Warsaw Uprising being the last battle of that campaign. The aftermath of the uprising was 180,000 dead and the destruction of the city of Warsaw.

We visited the Mausoleum of Struggle and Martyrdom (Mauzoleum Walki i Męczeństwa), the former Warsaw headquarters of the Gestapo on Szucha Street. There was a brief film that showed many of the victims of the Gestapo. This was a pretty depressing place, down in the basement with a row of isolation cells. Interrogations of prisoners who had been transported from St. Pawiak Prison were upstairs, and we did not get to see this area, but it was all gruesome enough based on Eva's description.

On the bus, Eva described the brutality and assassination of Franz Kutschera, the leader of the SS in Warsaw. On February 1, 1944, he was gunned down in front of the SS headquarters. In reprisal, the Germans executed 300 Polish civilians. We had an unhosted lunch at Elektrownia, a 1904 electric power station that is now a fashionable shopping mall with a great food court. I had a giant hot dog! Then we returned to the Citadel, the area that we visited two days ago for the Polish Army Museum. The Citadel was built in 1835 by the Russians as a warning to Warsaw residents after the uprising of November 1813. All of the original barrack buildings are gone, replaced by museums, but the "Tenth Pavilion” remains. This was where the Soviets brutally interrogated prisoners and tried them in a military court.

As we walked through the Citadel, Eva described the career of Tadeusz Kościuszko, leader of the first Polish national insurrection. As a general, he won some important battles for the Poles, but he also traveled to America and assisted George Washington's army with the construction of fortifications, including West Point. He has a bridge named after him in New Jersey. We encountered a number of Polish soldiers marching around the Citadel in preparation for some ceremony that we did not understand. Today was a day in which all the museums were closed.

We spent the remainder of our time on the Katyn Massacre. As background, Eva talked about the enmity that Stalin had for the Poles and how in 1937–38 he killed about 100,000 of them. After the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and the Soviet invasion of Poland, almost a million Poles were deported from occupied Poland to Siberia, where many died. In 1940, approximately 20,000 Polish officers, policemen, and other officials were murdered by the Soviets and buried near the town of Katyn, Russia. In the 85 years since, there have been efforts to get Russians to acknowledge their culpability in this massacre, but they have been met by denials and obfuscation. Boris Yeltsin at one time turned over the names of about 4,000 dead, and historians have been trying to determine which of these were killed at Katyn and which were at four other sites. Although the museum was closed, there was a small memorial that allowed us to see plaques containing the names of over 20,000 dead.

We returned to the hotel for a little downtime after a long day of walking and standing around in the sun. Dinner was another buffet in the hotel. We had to pack up our suitcases and turn them over to the hotel tonight in preparation for an early morning departure by train tomorrow; the bags will be traveling even earlier with Sylvester on the bus.