Hal Jespersen's V-E Day Tour in Germany, May 2025 [Part 3]

This is my report on a trip to Germany to commemorate the end of World War II in Europe (V-E Day), hosted by Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours. This is my fifth outing with SAHT and the third led by historian Chris Anderson. The most recent one was here. Last fall I did a different tour of WWII Germany, described here, so there will be a little bit of overlap. The report is long with a lot of photos, so I have divided it into three parts:

- Part 1: Touring Frankfurt and Heidelberg before the Ambrose tour started

- Part 2: Remagen, Dortmund/Ruhr, Paderborn, Mittelbau-Dora, Leipzig, Colditz, Dresden

- Part 3: Torgau, Potsdam, Wannsee, Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, Küstrin, Seelow, Berlin (this page)

Saturday, May 3 — Torgau and Potsdam

We took an early morning walk to Alt Markt. Chris gave us more accounts of the bombing. This square is known as the “burning place” because the SS from the camps had to be called in to burn unmanageable numbers of bodies in mass pyres.

As we drove north along the Elbe River, the weather turned foggy, damp, and cold. We reached the town of Strehla where at 12:30 p.m., April 25, First Lt. Albert Kotzebue (273rd Infantry, 69th Infantry Division) crossed the Elbe in a boat with three men of an intelligence and reconnaissance platoon. On the east bank they first met a Soviet horse rider, belonging to forward elements of a Soviet Guards rifle regiment of Konev’s First Ukrainian Front, under the command of Lt. Col. Alexander Gordeyev. On the 22nd the Germans had blown up pontoon bridges used by troops and civilians fleeing from the Red Army, killing and wounding hundreds and many of the bodies still covered the area on which we stood, at a ferry terminal with some commemorative markers in three languages.

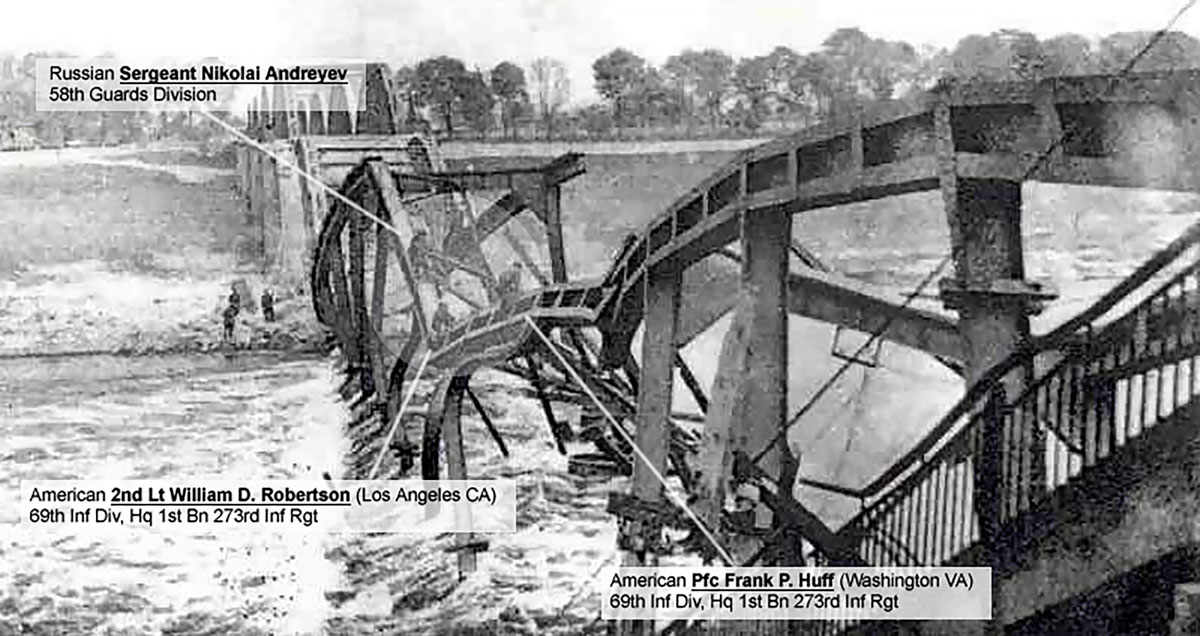

Although Strehla was the first contact between the armies, the second and more famous one was at Torgau, less than 20 miles downriver. This is my second visit here, the first last fall. The riverfront view is dominated by the imposing Hartenfels Castle, built in 1534, which we didn’t visit. Three hours after the Strehla encounter, another patrol of the 273rd, under Lieut. William D. Robertson, came upon a group of Soviet infantrymen near Torgau. Inching out onto the girders of the wrecked bridge over the Elbe, Robertson embraced Lieut. Alexander Silvashko of the 173rd Rifle Regiment. Staged photos of senior commanders meeting with handshakes were taken on April 26. The current roadway bridge is entirely different in design from the blown-up 1945 version. There are two Soviet monuments. We recreated a famous photo of US and Soviet soldiers posing on that exact spot in a Torgau street. Torgau is also noted for its role as a military “justice” center, where at least 1200 executions were carried out, and we passed by one of the buildings involved in this, but didn’t investigate. (Some of the following photographs are from my October 2024 visit, so the weather looks a little dreary.)

Next, we proceeded north for almost two hours, watching yet another World at War episode and eating a bag lunch from the hotel. We arrived at Halbe, 30 miles southeast of Berlin, the location of the battle fought between the German Ninth Army and the First Ukrainian Front. The Ninth Army had been pushed back from Seelow Heights and other positions on the Oder and encircled on April 22 between Marshal Konev’s front and Zhukov’s First Belorussian Front and made three attempts to break out from the Kessel von Halbe (Halbe Pocket) to potentially link up with the Twelfth Army and either defend Berlin or retreat to surrender to the Americans. The final attempt on April 28, threading the eye of the needle, resulted in fierce fighting and mayhem in the town, particularly on the main street at the railroad crossing. Casualties are difficult to quantify, but some figures I found for the Germans were 30,000 killed, 25,000 escaped the pocket, and 10,000 civilians were killed.

As we stood outside a man invited us into the nearby Kaiserbahnhof, which was a private railroad station used by three successive emperors. They came here for an afternoon of hunting in the Spree forest and accumulated so much game that they only returned every five years. It survived the battle, but there are still bullet holes visible.

Next the Kriegsgräberstätte Waldfriedhof Halbe (Halbe Forest Cemetery), the largest military cemetery in Germany. Figures vary, but there are possibly 28,000 dead here, many unknowns. It’s quite understated, unlike the majestic American cemeteries in Europe.

Another hour on the road to Zossen, the command center for much of the war’s operation (not including Hitler’s personal meddling from his various headquarters). We had a nice young woman, Francisca, conduct a two-hour tour. We started outside, walking past destroyed bunkers in the area called Maybach I, twelve buildings that hosted the Oberkommando des Heeres (High Command of the Army, abbreviated OKH). A similar complex nearby, Maybach II, hosted Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, or all of the armed forces, but all of those buildings were gone. Each of the buildings we saw was once 50 m tall, including two stories underground, and 36 m long, constructed so that they looked like large civilian houses from reconnaissance aircraft. The Soviets attempted to demolish them all, but the construction was so massive and strong that they were only partially collapsed.

A separate compound was called Zeppelin, and this was entirely underground. It was the communications complex for both Maybachs. The Soviets actually used this after the war, so although it was quite decrepit and littered with junk, we were able to go through it. We entered through chambers meant to defend against CBR attacks (chemical, biological, radiological) and descended 80 m for a long walk through many chambers and corridors. We saw photos of telephone, teletype, and radio rooms, and it was interesting to see elaborate pneumatic tubes for transporting written messages between complexes. On a couple of occasions, the lights went out temporarily, which was pretty creepy. It was chilly underground, but when the communications equipment was in use by hundreds of technicians, the heat averaged 35°C (95°F).

Then another hour on the bus to Potsdam, along with another World at War episode. Our hotel is Mercure Hotel Potsdam City, which is a step down in quality from the mostly Steigenberger brand we’ve been using, but still comfortable. We had a chicken dinner in the hotel restaurant.

Sunday, May 4 — Potsdam

We slept in a bit, and our first stop on a cold, blustery morning was the Glienicker Bridge, the famous Cold War “bridge of spies” that separated Brandenburg (East Germany) from West Berlin. Probably the most famous spy exchange here was Rudolf Abel for Gary Powers. During the war, this was the site of a lopsided fight between the 20th Panzergrenadier Battalion and massive Soviet units trying to get into Berlin from the west.

Next was the mansion in which the infamous Wannsee Conference was held in a swanky suburb fronting on Wannsee Lake. This was the January 20, 1942, meeting called by Reinhard Heydrich to determine the “final solution“ to the Jewish problem. Although as many as 900,000 had already been killed by this time, and the decision to kill all the rest of the Jews had already been made at the highest level, the 90-minute conference worked out some of the logistical details of how the various state ministries and the SS could deport millions more to occupied Poland and murder them.

We got a 90-minute tour. Our guide covered the history of the house, the conference, and what happened to the participants. The exhibits in the mansion cover the general situation, the conference attendees and agenda, the Protocol (essentially meeting minutes) they agreed on, the Holocaust itself in general, and the history of how this site has been handled since. Reproductions of many of the Protocol document pages are available, and good English translations are included. Although thirty copies of the Protocol were produced, only one copy survived, discovered by US forces in 1947 after it had been stored away in Martin Luther’s 1945 Foreign Service files in Thüringen.

We visited Schloss Cecilienhof, built 1913–17 for Crown Prince Willie, but famous as the site of the July 1945 Potsdam conference between Truman, Churchill/Attlee, and Stalin to map out the occupation of Germany and get Stalin’s commitment to join the war against Japan. The large complex was closed, so we could not see the interiors, but we walked around the outside and talked about this and the other two Big Three conferences. Then we were on our own for lunch in Potsdam. I had a decent pizza in a low-down shop called PiPaSa (Pizza, Pasta, Salat).

We visited the Garnisonkirche (Garrison Church) in downtown Potsdam, which looks very modern. Its tall steeple was damaged in the war and demolished in 1968, replaced by a different tall structure that has an observation tower. The remainder of the church has been remodeled to be significantly smaller than the original. There is just a small chapel inside now, but also a stylish museum about the church’s history. The reason we’re here is to remember Potsdam Day, March 21, 1933, when Hitler restarted the Reichstag here after the big fire. The date was the anniversary of the start of the very first Reichstag and the location significant in Prussian history, including the church’s burial places of Frederick William I and his son Frederick the Great. Photographs of Hitler greeting President von Hindenburg with deference led some to think that the new chancellor was more moderate than his reputation.

We drove to the town of Spandau, west of Berlin, watching the movie Cabaret. We stopped at Stresow Park with a view of the Charlotten Bridge. Berlin was encircled by April 27 and this bridge was the only way out. Chris read us an account of one of the German participants in the unfolding disaster. We had dinner on our own tonight. Many of the group had had a big lunch, so skipped dinner. I walked into town and found a take-out sandwich.

Monday, May 5 — Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen to Berlin

We drove about 90 minutes north of Berlin to the town of Fürstenberg and the Ravensbrück concentration camp. This is the seventh camp I have visited in the last year (well, eighth if you count the tiny Niederhagen at Wewelsburg), but the first one to imprison primarily women. Along the way, we watched the 2001 movie Conspiracy, about the Wannsee conference. It’s noticeably colder than last week, and I regret leaving my gloves, puffy vest, and warm hat in the suitcase stashed in the bus cargo hold.

We had a two-hour tour of the camp. There isn’t much to see other than a few remaining buildings, which we didn’t enter, and a memorial area with lots of plaques and flowers. Yesterday was a big ceremony in conjunction with the camp liberation anniversary, which was April 30. Near the camp entrance is a nicely preserved Soviet SU-122 self-propelled howitzer to mark that liberation. There were about 132,000 women in the camp during the war, including about 48,500 from Poland, 28,000 from the Soviet Union, almost 24,000 from Germany and Austria, nearly 8,000 from France, almost 2,000 from Belgium, and thousands from other countries, including a few from the UK and the US. More than 80 percent were political prisoners.

We started our tour in the female guard housing area, which is now a youth hostel. There were 3,600 guards, and more were here temporarily for training. After the war, it was the second-largest Soviet army camp outside the USSR. Most of the women prisoners worked in textile factories. There were also some male prisoners segregated in their own area, who worked on construction projects. Many prisoners were employed as slave laborers by Siemens in subcamps. There were gruesome medical experiments performed on a few hundred inmates. About 800 children were born in the camp; only 18 survived. We ended our visit in the crematorium. The gas chamber building is no longer there, but it killed about 7,000 people.

Our second stop was about 30 minutes south, Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Oranienburg, which I visited last year. Along the way, Chris told us a chronology of the concentration camp system. We were pleased that our Ravensbrück tour guide, Boris, found himself available for the first hour of our visit. Sachsenhausen was opened in 1936 primarily for political prisoners, but being close to Berlin, it served as an SS training course, and many of the graduates went to lead other concentration camps. It was the headquarters of all the German concentration camps. It also was the place in which mass execution systems were researched and perfected. The place is really big. Most of the buildings are only foundations now, but there are excellent maps and signage. A number of the remaining buildings contain specialized exhibits. Prominent is a 40-meter monument erected by the Soviets. Nearby is a long camp wall with numerous displays about prominent camp personnel and the evolution of execution methods. Behind it are a well-preserved execution trench (gruesome to contemplate) and a building called Station Z, a crematorium and place of extermination—10,000 Soviet prisoners were executed with a bullet to the back of the neck—with a moving memorial to the victims. About 200,000 prisoners came through Sachsenhausen; 32,000 died or were killed. The Soviets liberated the camp on April 22–23, finding only 3,400 prisoners. Earlier, the Germans had forced 33,000 to depart on a Todesmärsch (Death March) to the northwest.

Boris led us to a former building that was the camp brothel; prisoners who behaved well could be serviced involuntarily by women from Ravensbrück. Wandering on my own with an audio guide, I visited other areas. Soviet Special Camp Number 7 is an exhibit in a stern-looking, low-slung steel building. The Soviets liberated Sachsenhausen and then turned it into their own prison camp. The Prisoners’ Kitchen building presents the history of the camp. Barracks building 38 presents the Jewish prisoner experience, and Barracks 39 the everyday life of prisoners in general. The Infirmary Barracks covers the medical treatment and criminal medical sterilizations and experiments. There’s a building called the New Museum, but it is empty except for a large stained-glass window depicting 1961 East German regime themes. A series of modern buildings were the SS barracks, but they are now the Brandenburg University’s Center for Applied Police Sciences, which seems to be a questionable location. A ways outside the main camp area is the T Building with the exhibit “Center of Terror, the Concentration Camps Inspectorate 1934-1945.”

We drove about an hour to our new hotel, the Westin Grand Berlin, which is located in the Mitte section, formerly East Berlin. Quite fancy and conveniently located. Dinner on our own again. A group of us went out to a nearby restaurant/bar called Gaffel Haus and I had an excellent Currywurst, a Berlin specialty.

Tuesday, May 6 — Seelow Heights

Bright but chilly today. We drove about two and a half hours east to the Polish border and into the town of Kostrzyn nad Odrą (Küstrin an der Oder). On the road we watched multiple episodes of a BBC series called The Nazis. The drive was lengthy because the Route 1 bridge over the Oder couldn’t handle our bus, so we crossed way south at Frankfurt an der Oder and then drove north on the Polish side. Our visit to Küstrin, which was part of Germany in 1945, was to examine the Battle of the Oder–Neisse, April 16–19. This is usually conflated with the Russian attack on the Seelow Heights, starting the Battle for Berlin.

We were met by a local guide, Rafo, who described how the old fortress here, "Festung Küstrin,” was half demolished in the 20s, but it was originally the borders of the Altstadt. It was a difficult place to attack through because it spanned an area between the Oder and Warthe Rivers and there were only a few bridges. As we walked into the old city, we were amazed that it was essentially obliterated. The war ruins of the old city had been bulldozed over and only woods remain. Chris called it Pompeii on the Oder. Rafo used large pre-war photos to orient us so that we could imagine where city hall once was, streets (still identified by signs) were, etc. Many of the bricks were transported away to rebuild Warsaw. He showed us where admiral Tirpitz lived.

Rafo described how Hans Reinefarth, who had commanded during the Warsaw uprising, attempted to defend Küstrin.he criticized the Soviet tactics, describing how a column of Sherman and Valentine tanks, advancing without infantry cover, was decimated by German Panzerfausts. And how Panther tank turrets were in fixed defensive positions on the river bank. Inside Bastion Filip (Philippe) we visited Muzeum Twierdzy Kostrzyn, which is nice, modern museum, but not a word of English was employed in the displays.

We delayed briefly to run into a gas station to supplement yet another hotel-provided bag lunch. Then back south to cross the border at Frankfurt an der Oder. We visited the Kriegsschauplatz Schloss Klessin, the site of a fierce battle in February–March. There is a geological formation called the Reitweiner Sporn (Spur, née Nase/nose) that is a low ridge parallel to the Oder, but one that commands the lower ground (the Oderbruch floodplain) through which the Soviets needed to advance. There is a foundation for a large mansion (the Schloss) that was defended by the small 1242nd Infantry, about a quarter of whom were military officer cadets. They have a steel structure showing an outline of how they moved a Hetzer tank killer through the front door into the house. (There were also two Panthers that participated.) The Soviets encircled the area in February, and the defenders fell on March 23. The wayside exhibits here are modern and excellent.

In the town of Reitwein, we climbed up a hill on the spur to see an impressive church, the Stüler-Kirche. Zhukov’s CP was about 1km south of here, but we did not have time to make a hike to see it. (I found photos on the Internet.) He had sort of a log cabin bunker, and there are supposedly visible trenches to see in the area. But this was the position that was essentially the start of the Seelow battle we’ll see next.

Next, Seelower Höhen (Seelow Heights), site of the critical initial assaults in the Battle of Berlin, beginning on April 16. This was another place I visited last October, but today was a superior experience. There is a museum and memorial. We started with an excellent 30-minute movie about the battle, which focused on eyewitness testimony from German civilians and soldiers. And they had a cool 3-D terrain map in the theater, but inadequate lighting for a good photo. The museum itself is quite basic with more information about creating the memorial than about the battle and a few artifacts. Outside in front are a T34-85, a rocket launcher truck, and a couple of artillery pieces. Climbing a hill, we visited a Soviet victory monument and got a view of the battlefield terrain, the Oderbruch, below. At the monument, Chris gave us a good overview of the conduct of the battle and explained the importance of the Hauptgraben canal/tank barrier, which we crossed over in the bus, as well as other important terrain features.

It was about 90 minutes back to the hotel, with yet another episode of The Nazis. Dinner was in the hotel restaurant. Excellent meal, although not very Germanic.

Wednesday, May 7 — Heading Home

Because of a travel conflict I have coming up this weekend, I needed to get back to the United States before the tour completed. I arranged this with the SAHT staff, and they were very gracious in accommodating me. Last fall, I stayed in Berlin for three days (see here) and visited a number of locations that are in the aggressive plan for the remainder of this trip. I am also considering another trip this fall with Chris Anderson that covers Poland and Berlin. For completeness, here is a list of the places scheduled to be visited by the group in the four days I will not be able to attend. I have annotated the list by italicizing all of the places I have already visited.

- Olympic Stadium

- Hitler’s Bunker & Chancellory Site

- Former Lutwaffe/Air Ministry Building

- German Resistance Memorial Center

- Treptower Park

- Museum Berlin Karlshorst

- Topography of Terror

- Neue Wache Memorial

- Stasi Prison

- Bernauer Strasse Berlin Wall Memorial

- Checkpoint Charlie

- Tempelhof

- Brandenburg Gate

- Reichstag

- Soviet War Memorial

- Moltke Bridge

- Holocaust Memorial

- Anhalter Bahnhof ruin and air-raid shelter

- Old Jewish Quarter of Berlin-Mitte Hackescher Markt

- Otto Weidt Museum

- Allied Museum

It was sad to miss the official V-E Day, May 8, in Berlin, but I actually prefer May 7, when the German armed forces surrendered to Eisenhower in Reims.

My flight back home was to Munich on Lufthansa and then United direct to San Francisco. I had an excellent time on this Ambrose trip with Chris, Connie, and Klaas. I learned a lot and saw important sites in Germany I had never visited before, despite a few overlaps with previous trips.